Hall of Fame profiles: Cheryl Robinson

No one in the Women’s Professional Bowling Association had ever seen anything quite like Cheryl Robinson.

No one in the Women’s Professional Bowling Association had ever seen anything quite like Cheryl Robinson.

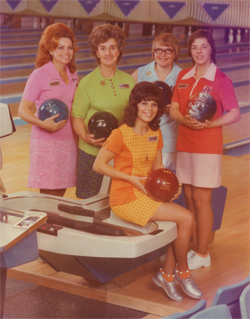

She was “the brunette with flashing brown eyes that seem to smile perpetually,” as one 1970 Bowlers Journal story put it. She was the 1970 Alberta E. Crowe Star of Tomorrow, and she was just as likely to land roles in Hollywood as she was to score on the lanes.

The former member of the now-defunct Screen Extras Guild, who landed minor roles in several films and even a TV show in her heyday, brought a charismatic charm and movie-star looks to a ladies’ tour dogged by the perceptions of female pro athletes that prevailed at the time.

“At that time, women pro athletes were perceived as being more masculine than feminine, and there was a lot of talk on the ladies’ tour about there being an image problem,” says two-time ladies’ tour titlist Leila Wagner. “Cheryl helped change that. She was feminine, married, and she and her husband Jay were just known as this perfect bowling couple. As a 15-year-old girl, I remember thinking ‘Oh, that’s going to be me someday! I want that life someday.’”

That is the Cheryl Robinson that comes immediately to the mind of Judy Soutar, who, along with her husband, PBA and USBC Hall of Famer Dave Soutar, knew the life Leila Wagner dreamed of as well as anyone.

“Cheryl was very cute and bubbly and she’d just get so excited when she bowled good,” Soutar says. “Back then people would say ‘Oh, you’re a woman bowler. You’re supposed to be 200 pounds and have biceps’ or whatever. But between her and Leila Wagner, they kind of really changed the image of professional women’s bowling.”

But anyone tempted to dismiss Robinson as just some pretty young face that would come and go on the ladies’ tour soon found themselves hugely mistaken. Robinson would win her first tour title a week before her 21st birthday in 1972. In that year alone, she would finish fourth in the U.S. Women’s Open, eighth in the PBA National Championship, and fifth in the USBC Queens, where she also would set a tournament record at the time with a four-game series of 995.

“It was an amazing feat to come out on the ladies’ tour and win at the age of 20,” Wagner says. “Especially back in the ‘70s. She had to beat the Judy Soutars and the many other great players on tour at that time.”

By then, everyone on tour understood that a battler lurked behind those smiling eyes, that the Hollywood charm bowling writers adored belied the intensity of a born competitor.

“I joined the tour in 1960 and finished second 13 times before finally winning in 1973, so Cheryl won before I did!” Soutar recalls. “She never gave up. I don’t care if she had to have 280 in her last game to make match play, she started that game with the idea that she was going to bowl 280. And many times she would bowl a huge game to make it. Cheryl was in that elite group who could adjust to any condition. She was always in contention.”

That was the Cheryl Robinson the ladies’ tour contended with, the southern California girl who thought nothing of joining a Los Angeles Junior All-Star Traveling League in which she would be the lone girl competing alongside 29 boys.

“Most of them didn’t care,” Robinson said in 1974, “but I beat one guy in a rolloff and he went out to the parking lot and sulked for a long time.”

Robinson would leave plenty of players sulking in the years to come, winning three more titles and landing another top-10 finish in the Queens, finishing runner-up to Donna Adamek in 1980.

“Getting into the Hall of Fame really humbles you and makes you look back on a lot of things,” Robinson says.

Robinson has just as much to look back on as she has people to thank.

People like the girl who first introduced a 10-year-old Robinson to the sport by inviting her to a bowling birthday party, or the mother who promised not to make her pay for practice out of her allowance as long as she bowled over her average.

People like coach and proprietor Tosh Kinjo and the many hours of free practice he gave her at Holiday Bowl, or the AMF staff that sent her trotting the globe from Denmark to Japan, Spain to Moscow and many stops in between doing clinics and exhibitions.

“Something I always wanted to do was travel,” Robinson explains. “I was one of the lucky ones that got on the Staff of Champions at AMF. There were a lot of bowling centers opening up abroad at that time, and I was lucky to be able to do exhibitions and clinics with Dick Ritger. We did quite a bit of work.”

No one travels the road from a bowling birthday party to the USBC Hall of Fame without “quite a bit of work.” Sure, there may have been a brush with luck here or there, a change of fortune that easily might have gone the other way. But this is Cheryl Robinson, the one who once openly favored a career on the lanes over a career on camera.

“I wouldn’t want a career as an actress,” she told one bowling writer in 1970. “I’ve got bowling and other interests.”

This is the Cheryl Robinson who, when asked during her first pregnancy when she planned to give bowling a rest for a while, answered that she would do so only when she could no longer stoop over to tie her shoes. “I won a title when I was six months pregnant, and I did so knowing how well Cheryl bowled when she was pregnant,” Leila Wagner recalls. “I remember thinking to myself ‘If Cheryl was doing this then I can do it.’”

“I won a title when I was six months pregnant, and I did so knowing how well Cheryl bowled when she was pregnant,” Leila Wagner recalls. “I remember thinking to myself ‘If Cheryl was doing this then I can do it.’”

It is the Cheryl Robinson who derived her focus from the thoroughbreds she read about.

“I have a story I came across that explains that,” Robinson says from her Placentia, Calif. home. “It was put out by the actress Marlo Thomas. When she became a star she was afraid and wanted to change her name, and her father got upset with her and said he raised her to become a thoroughbred, and thoroughbreds run with blinders on and keep focused on the straight-ahead with no distractions. I just think you’re running your own race and you have to know your game well enough to be able to have the strength and stamina to do it.”

For many of the young women who thought they had what it took to compete on the ladies’ tour and went out to give it a try, that race ended about as soon as it began. But for Robinson, that race still has several laps to go. It will land her officially in the USBC Hall of Fame on July 1, and it will take her to another shot at glory later this month, when she will put those blinders on once more and hit the lanes for the 2011 U.S. Women’s Open.

“I plan to compete in the U.S. Open before the induction ceremony,” she says. “I have been practicing since February trying to get back in shape, and I am excited about it.”