Meet the Double Lung Transplant Recipient Who Advanced into the WSOB X Field

UPDATE: APRIL 12, 2019

We are devastated this morning to learn that David Williams Jr. died in a car accident yesterday on his way to the upcoming PBA50 Tour stop in Clearwater. His wife Sheri reported the terrible news on Facebook last night. Our thoughts are with the Williams family.

David Williams Jr.

David Williams Jr.

Fifty-three-year-old PBA Regional champion David Williams Jr. says it made him “happy” to have advanced into the WSOB X field after finishing third in the event’s pre-tournament qualifier on March 10. Less than a year earlier, he was happy just to be alive.

For the past 15 years, it was easy to spot Williams in a PBA tournament. He was the guy who spent his time between shots self-administering the supply of oxygen he took with him anytime he went bowling.

“I would basically wear my oxygen, and then when it was my turn to bowl, I’d take it off for a little bit,” explains Williams, who joined the PBA in 1992. “And then, as soon as I took my shot, I had to put it back on. I was on about ten liters of oxygen, and I still was shooting 300s and bowling on the tour out there. I was just carrying my oxygen bottles. I was still cashing.”

In fact, Williams did a lot more than cash. Throughout much of the time his health forced him to pack oxygen tanks along with his bowling balls any time he hit the road for a tournament, he won two standard PBA Regional titles — a 2011 event in Chillicothe, Mo., and another in Lockport, Ill., in 2015. He added one PBA50 Regional win in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 2016.

In 2006, Williams made national bowling headlines when he posted a 783 set in singles at the USBC Open Championships on scores of 267, 279 and 237 to sit in sixth place in that portion of the event at the time. He finished that tournament with an all-events pinfall of 2,008.

“I just felt like I still could compete,” Williams says of his will to continue bowling in spite of his health challenges. “I still was averaging over 230 while sick. My game wasn’t really slipping; it’s just that I had to take my time. I couldn’t go as fast. I still had the ability. I just couldn’t keep up with the pace.

“Like, if I made the finals or something, the guys would wait on me on the tour because they knew I was sick. They just told me to take my time. That was pretty relaxing; the guys were pretty understanding. Me and Pete Weber and Walter Ray , we all became really good friends. When you win out there, those guys really respect you.”

A Nebraska State and Omaha USBC Association Hall of Famer, the Omaha native’s success has not been limited just to regional action or annual tournaments like the Open Championships. In 2017, he made match play at the PBA50 UnitedHealthcare Sun Bowl in The Villages, a national stop on the senior circuit, and averaged 232.61 for 24 games. His 17th-place finish in that event was better than Pete Weber, who finished 21st, and Ryan Shafer, who finished 19th.

“He showed up at The Villages with an oxygen tank to bowl,” says Bo Goergen, who finished 12th in that event. “He had been bowling with an oxygen tank for a couple years prior to his double lung transplant.

“My history with David goes way back. I am originally from Sioux City, Iowa, which is about 90 miles from Omaha, so we competed back in the day. And you want to talk about the heart of a lion? Holy smokes! He is a true competitor.”

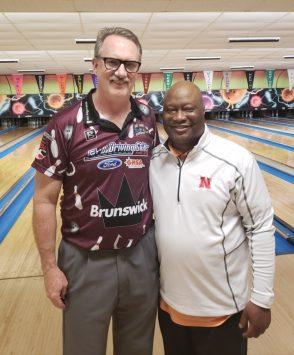

Walter Ray Williams Jr. called David Williams Jr.'s success in the WSOB X pre-tournament qualifier following a double lung transplant "absolutely amazing."

Walter Ray Williams Jr. called David Williams Jr.'s success in the WSOB X pre-tournament qualifier following a double lung transplant "absolutely amazing."

The prior year, Williams cashed in the same event in The Villages, finishing higher than PBA Hall of Famer Bryan Goebel as well as other former PBA Tour stars such as Bob Learn Jr. and John Gant.

Williams remembers vividly the day his lungs began to fail him. He was at work, selling cars for Chrysler, when suddenly an average day on the job turned out to be the day his life never would be the same.

“I was just having a hard time breathing,” he recalls. “I told my friend that I was having trouble breathing and he’s like, ‘Man, are you okay?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t think so.’ So they took me to the hospital. The first doctor said I need to see a specialist. I went to see the specialist, and then he said he thought I had cancer. I’m like, ‘Cancer? Man, I ain’t got no cancer. I never smoked!’”

Williams headed to another specialist to get a second opinion. It did not turn out well.

“The other doctor told me that I had sarcoidosis,” Williams says. “I said, ‘What is that? I ain’t never heard of no sarcoidosis.’ He explained to me that it is more common in black people than it is in whites, and that it’s basically a hereditary disease. He said it was gradually going to get worse over time.”

Sarcoidosis is incurable, the doctor told him.

The news kept getting worse. His lungs deteriorated over the years to the point that, eventually, “They gave me a year to live,” Williams says. “That’s what pushed me to get the lung transplant.”

That’s also what pushed him to bowl the PBA50 Tour.

“His basic thing was, when he turned 50, he wanted to bowl because doctors told him he didn’t have a lot of time left, so he wanted to go out and bowl the senior tour,” says Walter Ray. “It was just one of those lifelong dreams, and unfortunately it was cut short due to what happened to him in Arizona.”

What happened to David Williams Jr. in Arizona was something Walter Ray describes as “eye-opening.”

“About three years ago, we were bowling a regional up in Arizona, and he was having a lot of trouble breathing because he was having his lung issues, but also we were in Flagstaff, which is like 7,300 feet above sea level,” Walter Ray explains. “ Tommy Martin took him to the quick care place and then he ended up in the hospital, and he hadn’t told anybody about what was going on with him.

“He mentioned to Tommy that he needed a lung transplant and all this, and we’re like, ‘Oh, my God!’” Walter Ray says. “It’s pretty remarkable to see at the World Series this last month. For him to make that recovery from traumatic surgery, that’s absolutely amazing. Coming off a major surgery like that, you just want to be able to wake up the next morning. I can’t imagine what he’s gone through the last couple of years.

“I think he’s a bit on the humble side,” Walter Ray adds. “I don’t think he wanted to advertise that he’s had these health issues.”

For Goergen, the David Williams Jr. he saw advance out of the PTQ field at WSOB X was the David Williams Jr. he always has known.

“When I was watching that PTQ from home, man, I was rooting for him. I thought that was fabulous,” Goergen says, “just because I know what kind of heart he has, and his passion for the game. And he still throws it phenomenal. It’s not like he’s ever been challenged with his physical ability. Sure, like all of us, there are times when he doesn’t match up or things don’t work out, but it’s never been because of his physical ability, as his resume indicates.”

David Williams Jr. used GoFundMe to raise $6,000 for expenses in advance of his double lung transplant on March 29, 2018. Less than a year later, the PBA Regional champion was bowling professionally again.

David Williams Jr. used GoFundMe to raise $6,000 for expenses in advance of his double lung transplant on March 29, 2018. Less than a year later, the PBA Regional champion was bowling professionally again.

Williams got his new set of lungs on March 29 at the University of Iowa hospital, less than a year before he finished third in WSOB X’s pre-tournament qualifier ahead of Kenny Ryan, who went on to finish sixth in the 2019 USBC Masters on April 1, nine-time Team USA member David Haynes, and 12-time PBA Regional champion Lee Vanderhoef, among other notable PTQ competitors.

What’s more, he had only returned to bowling about four months earlier.

“It took me about eight months after the lung transplant The first day I came back, I shot 300,” Williams says, chuckling.

He had a good chuckle with the surgeons heading into his March 29 transplant procedure, too.

“They wheeled me down, and I was talking to the guy, and I said, ‘Man, I sure hope ya’ll know what you’re doing.’

“They said, ‘You’re funny!’ I said, ‘Man, I’m not trying to be funny!’

‘I was scared,” Williams adds. “I tried to get my life in order with God and with people I knew and with my life insurance policies, just trying to make it easy for anybody that I would be leaving behind.”

Williams says his last thought before going under for the surgery was, “I sure hope I wake up. If I could just have a chance to wake back up, that would make me happy.”

When he did wake back up, he wondered if he was in heaven.

“My mother and my wife were standing above me and they said, ‘You had your transplant.’ And I’m like, ‘What?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, it’s all done.’ I couldn’t talk, but I was in a lot of pain. They just told me to be still. There were like 20 people in the room and I was like, ‘Man, am I in heaven? Where am I at?’ I see all these people and you’re still on anesthesia, and you’re not really aware of the whole thing, but I know I saw a whole lot of people, and I was thinking in my mind, ‘Are they real?’

“I just ended up going back to sleep, and then they had me in the ICU for about a week and they would get me up to walk maybe 10 steps and then they’d put me back in the wheelchair. They just wanted to try to get my lungs to circulate some; they don’t want you just laying down. They want to get the lungs moving.

“It was a long process. Very demanding, very frustrating, very painful. I mean, they cracked my whole chest open, they broke all my ribs. It hurt so bad. I’m just thankful to still be alive, and to be able to still bowl. I don’t know of many people who have had a double lung transplant who are out here doing what I’m doing.”

Compounding Williams’s gratitude that he still is alive is a fresh perspective on how to live the years he has left.

“Hatred is a bad thing,” he says when asked what it took to get things right with God before his surgery. “I’ve never hated anyone in my life. If I did someone wrong, I wanted to make sure I apologized. I just kind of cleaned my life up in terms of giving God a lot more attention and trying to get a better understanding of what he wants from us in our lives.”

Says Goergen: “He is one of the most genuinely nice guys you’ll ever meet. He goes out of his way to help anybody in any way, shape or form.”

Williams used GoFundMe to raise $6,000 for expenses in advance of his surgery; Goergen was among those who donated. These days, Williams depends on a daily dose of “anti-rejection” medications to ensure his body continues to work with his new set of lungs. He will have to take those medications for the rest of his life.

“It’s a lot of pills, but that’s just what I gotta do to live and be happy,” he says.

When the PBA50 Tour gets started later this month with the PBA50 Johnny Petraglia BVL Open at Countryside Maple Lanes in Clearwater, Fla., David Williams Jr. will be there, shoeing up alongside legends such as Weber and Walter Ray and Brian Voss, Parker Bohn III, Amleto Monacelli, Johnny Petraglia and others.

And when he does, he will know one thing: While those aforementioned names have won more titles than he has, none of them will have faced down the odds Williams overcame just to have the chance to compete among the greatest bowlers in the world.