Born to Bowl: How the Shock of Mark Roth's Talent Changed Bowling Forever

BY LYLE ZIKES

Still in bowling attire, the rookie sat on the edge of the bleachers at Westgate Bowl, site of the PBA’s 1970 Grand Rapids Open, watching the afternoon squad. Anxious, a pack of cigarettes by his side, he engaged in a brief conversation with my dad, USBC Hall of Famer and PBA Tour champion Les, as I stood by.

After a casual introduction, dad said, “Mark’s at 36 . Ever see him bowl?”

Yes, I knew Mark Roth stood precariously close to the projected cash line because I’d been watching him bowl all day.

I felt a little guilty about that. Naturally, I was there rooting for my dad, but that was before the peripheral vision of my 13-year-old eyes caught sight of a young, strong-armed player aggressively launching bullets down the lane with a violent amount of turn on the ball. Based on style, he looked like some local hot shot who didn’t belong in a pro tournament except, you had to admit, his bowling ball looked mighty impressive tracking toward the pins.

Intrigued, I made the unusual decision get a better look at this guy that the lane pairing’s sheet listed from Brooklyn, N.Y. He was 19-years-old at the time and looked it. The more I watched, the more captivated I became, enamored by a rev/speed combination I had never witnessed before.

Still, something seemed wrong. I had come to know bowling as a game of accuracy and precision. Given those priorities, if you could put an effective rotation on the ball within the confines of good form, all the better. Even as a young teenager, I knew longstanding instructional axioms like: “Make the spares, the strikes will come” and, “Learn to be a bowler, not a thrower.”

Roth’s technique violated a bunch of well-established norms. He took six steps… except when he snuck in a seventh. His footwork was rushed. His backswing was high. All of which was a recipe for malfunction except, in Roth’s case, his extraneous motion seemed to come together powerfully at the release.

Roth bowled like he was trying obliterate the pins at a time on tour when such animosity was considered misplaced, immature and counterproductive. Throwing hard meant you couldn’t apply enough quality side rotation and accompanying finger lift to get a bowling ball of that era to grip and hook a bit.

Roth’s unspoken response was, “Oh, yeah? Watch me.” You could endorse the man’s talent or you could dismiss it, but one thing you could not do was ignore it.

As his career steadily developed, viewers of PBA telecasts also became familiar with “the scowl,” especially when watching Roth react to shots from a front camera angle. Several years later, one bowling writer suggested that Roth hardly ever smiled because he was hiding his teeth. “That little bit of personal embarrassment affected his personality,” the writer came to believe.

Such speculation aside, it’s certainly true that Roth didn’t want to be interviewed on TV, especially at first. As he was gaining the top seeded position at the 1972 Brunswick World Open — his first PBA telecast — the 21-year-old said repeatedly, “I don’t want to talk.” Eventually, as my dad overheard him, he responded firmly, “But Mark, you have to talk.”

It wasn’t long thereafter that PBA TV Coordinator Frank Esposito took on a father figure role, advising the budding superstar of his responsibilities and business opportunities while sometimes cajoling him to soften his demeanor.

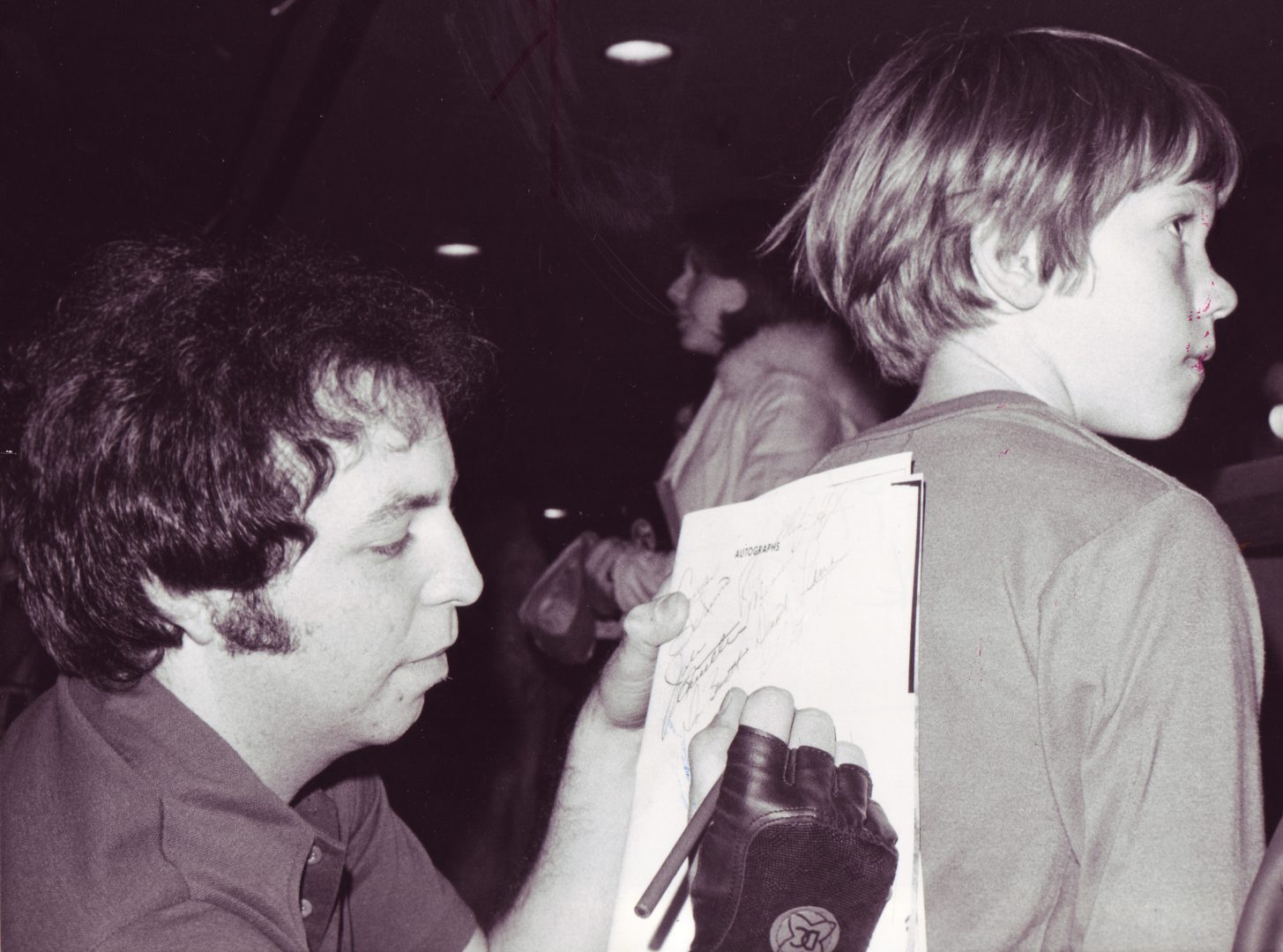

By the time I went to work for the PBA as a pressroom publicist in 1979, Roth was on his way to a third straight Player of the Year season and had stopped objecting to fulfilling media requests, especially when it was immediately after a round. Being able to follow me, or another coat-and-tie-wearing PBA staff member from the player’s paddock to the press area, provided an excuse to avoid untold numbers of fans clamoring for a post-round autograph or photo.

As an interview subject, the “New Yawker” who spent a quarter of a century as a New Jersey resident could give a frame-by-frame recitation of his round, as well as independent characteristics of every lane he just played on. If one ever accused Roth of being cerebral, still he was brilliant at recognizing ball-reaction variables and adjusting through alignment moves or simply intuition.

The media wouldn’t get meaty observations, clever analysis or anything provocative regarding another player. He didn’t regard other players dismissively in the least, even when the talent gap was indeed gaping. While some fans might have relished a more out-going, autograph-signing marquee personality, there was rarely a reason for another player to dislike Roth other than the fact that he was so hard to beat.

It might seem surprising that unlike many other big-name players, Roth, to my knowledge, was never fined for any kind of temper display at a tournament site. There were no verbal outbursts, no pounding on score tables or upending chairs, etc. Instead, it was said that he started a round already on edge and a bit agitated, and he merely kept that as an even keel. Besides, he had a certain doubles partner that was prone to more than enough temper-induced histrionics for the both of them.

Although Roth and Marshall Holman won their first PBA titles in the same year (1975), the East Coaster had been consistently knocking on door before breaking through for his initial win by shooting 299 in the championship game of a Winter Tour event in the Kansas City area — the 1975 King Louie Open at King Louie West Lanes in Overland Park. Meanwhile, Holman won his first two titles in non-televised events.

So, while both highly influenced changing the standard style of play among the best in the sport, Holman gets a supporting award while Roth duly maintains the title “Father (now Grandfather) of the Modern Game.” Not only did Roth proceed Holman, he defied more stylistic norms and he won 34 titles and four Player of the Year awards compared to 22 victories and one Player of the Year for the Oregonian.

By the early 1980s the Tour saw the likes of Dave Husted, Wayne Webb, Steve Martin, Joe Berardi, Bob Handley and, from the left side, Steve Cook, winning titles with hardly anyone suggesting they were too “hook obsessed.”

From a technical standpoint, Roth’s “hit up on it” release is now considered a relic of the plastic ball and early urethane days. But his devotion to the power game continues to inspire those who learn to “mega cup” a reactive ball so severely that they can generate an even higher rev rate by breaking their wrist back at the release point rather than upward.

Roth even began to modify the hit and loft on his release as he became age-eligible for the PBA Senior Tour in 2001. He was Senior Tour Rookie of the Year that first season and Senior Player of the Year in 2002, which included winning the $20,000 top prize in the Suncoast Senior World Championship, the forerunner of what is now the Senior U.S. Open.

His last significant victory wasn’t even a PBA event, rather the inaugural of the highly-ambitious, short-lived Generations Bowling Tour in Bay City, Michigan, worth $13,500. As a Senior-Tour bowler, Roth was more relaxed, and he looked forward to hanging out with his fellow competitors. Since he hadn’t experienced any long-lasting physical injuries despite his full-throttle, all-out exertion style, it seemed he would be playing against the over 50 crowd for quite some time.

Unfortunately, that plan ended with a debilitating stroke early in 2009. His ability to recover enough to attend some tournaments, particularly the Mark Roth/Marshall Holman PBA Doubles Classic, was a treat to his fans, but came with some sadness. The guy who once was almost too frightened to talk on television now had no problem speaking to the broadcasters, but, as implausible as it seemed, he so badly yearned to get out and compete again.

I suspect there are others like me who remember the exact place, date and circumstances when we first saw Mark Roth throw a bowling ball. Beyond all his titles and awards., that may be his greatest legacy.