How Bowling Bounced Back from Spanish Flu

BY J.R. SCHMIDT

In September

1918, as the new bowling season got underway, sports in America faced an

uncertain future. The United States had been pulled into the Great War in

Europe. The government was curtailing all activities that didn’t further the

war effort. “Work or fight!” the order went. Thousands of young men had already

been drafted into military service. The last month of the baseball season had

been cancelled, with the World Series held just after Labor Day.

Bowlers were

trying to continue on as best they could. Some leagues had folded, and pinboys

were getting hard to find. There was talk that next year’s American Bowling

Congress Tournament at Toledo might be called off.

In Chicago, Bowlers Journal was completing its fifth

year of publication. The Journal had begun as a weekly newspaper chronicling

the local bowling scene. But by 1918, Editor-Publisher Dave Luby already had

several correspondents sending him regular reports from the country’s main

bowling cities. Also featured were letters home from Dave’s sons, Mort and

Forrest, both serving with the U.S. Army in France.

The big Chicago

tenpin news was the follow-up to the previous spring’s Patriotic Bowling

Tournament. Local bowlers had staged the city-wide event in May, raising more

than $2,000 to build a bowling facility at the Camp Grant army post. That plan

had fallen through. Now it was announced that the money would be used to

install alleys at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station.

The leagues

started rolling. As usual, Bowlers

Journal printed weekly roundups from the Randolph, the North End

Traveling, and the city’s top house leagues. Gertrude Dornblaser reported on

women’s bowling. Luby’s correspondents in San Francisco, Cleveland, Minneapolis

and other cities checked in.

And now, as

September moved on, a new disruption to America’s everyday life began to be

felt — the Spanish Flu.

A century later,

there’s still no definite answer as to where or when this pandemic started.

Later it came out that there had been influenza outbreaks in different parts of

the world as early as March. But with a war going on, the governments in the

belligerent countries exercised tight control of the news, and the general

public knew little of these health concerns.

That wasn’t the

case in Spain, which was a neutral country without wartime censorship. So when

people began dying in Spain, that fact was reported in all the warring nations.

By June, the new disease was labeled — unfairly — the Spanish Flu.

Unlike most diseases, this flu was deadliest to people in their twenties and thirties. It came on quickly, too. A person would be feeling fine, then suddenly get headaches and fever, and start vomiting. Then he would turn blue and begin spitting up blood. Within a day or two, he’d be dead.

Large gatherings

of people were thought to spread the disease. In 1918, the United States had no

centralized center for disease control, no federal Department of Health. As the

new flu began to spread, individual city and state governments took whatever

containment measures they thought would work.

People tried all

sorts of home remedies. Hanging a bag of camphor around your neck was one

method. So was chewing plug tobacco. Apple cider vinegar, boiled red peppers,

honey-laced rye whiskey, and the old reliable — chicken soup — were other

treatments. Eating raw onions was a favorite cure, one that certainly kept

people from getting too close. Meanwhile, scientists labored desperately to

develop a vaccine.

On Oct. 4, Pennsylvania closed all places of public assembly. Philadelphia alone had more than 75,000 cases of the disease, with 139 deaths reported in the previous three weeks. Schools, theaters, churches, political meetings and sporting events were shut down. Soon, similar large-scale closings were ordered in Boston, St. Louis, Cleveland and Buffalo, as well as in hundreds of smaller towns.

Bowling alleys often

were included in these blanket shutdowns. By the middle of October, Dave Luby’s

correspondents were reporting that establishments had been shuttered in Minneapolis,

Milwaukee, San Francisco and Indianapolis. Yet in New York City and some other

places, alleys were allowed to continue operating. Bowling was considered a

form of exercise that would help a person remain physically fit and better able

to fight off the deadly flu.

Still, only

active bowlers were to be allowed on the premises. Proprietors were told to

turn away spectators and anyone else. And since fresh air was thought to

diffuse and weaken the virus, proper ventilation had to be maintained.

Chicago was one

of the cities where the alleys remained open. But most people were staying off

the streets, and a number of leagues cancelled sessions. Open play virtually

ceased.

Jimmy Smith was

bowling’s match-game champion. He had been contracted to bowl a series of

exhibitions in Chicago. On Oct. 14, he beat local star Frank Kafora in an 11-game

set at Randolph Recreation. The next day, Smith was on the train back to his

home in Brooklyn, the rest of his schedule scrapped by the flu.

On Oct. 19, Dave

Luby weighed in with a Bowlers Journal

editorial titled, “Keep the Alleys Clear and Clean.” Luby recognized that the

Spanish Flu had become “a serious menace,” something that everyone should be

concerned about. Still, there was no reason for the bowling community to panic.

Common-sense measures would help defeat the threat.

Luby urged

Chicago proprietors to keep their premises “well-ventilated, clean and

sanitary.” Crowds should not be allowed to gather. At the same time, bowling

must continue, since it was one of the best “health-givers” available.

“The influenza

germ has not yet been found in a bowling alley,” he concluded, “and it will not

be if the rules of sanitation are strictly adhered to.”

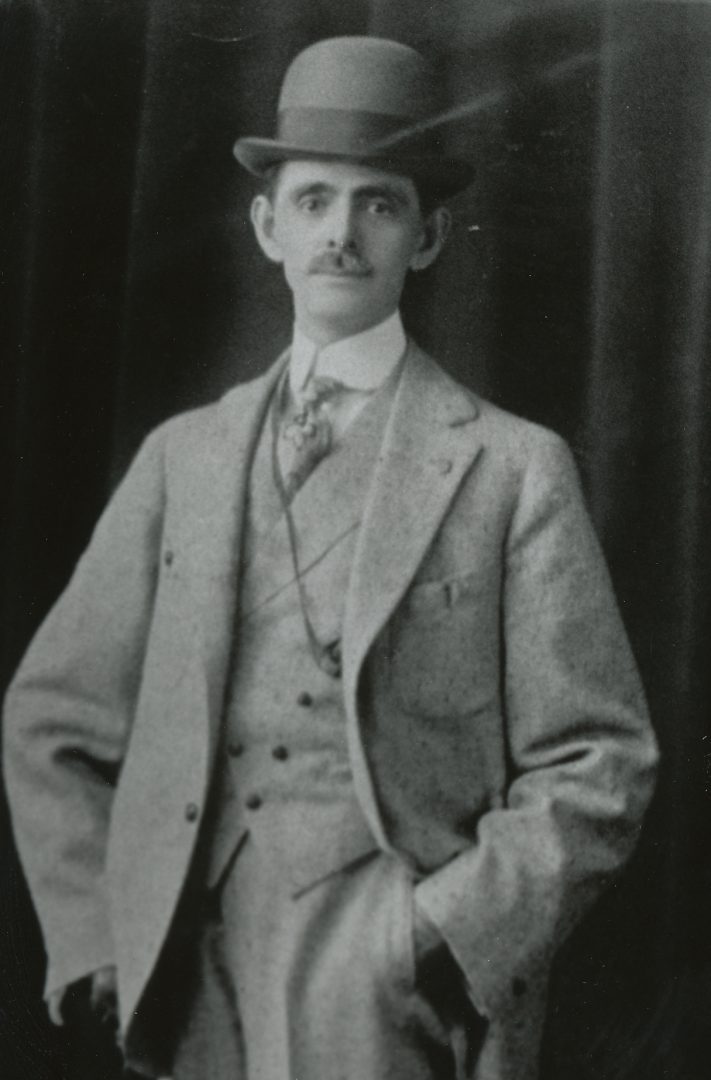

Bowlers Journal also

printed some practical advice from a flu survivor, none other than W.V.

Thompson. The Brunswick exec, often called “the final authority on all things

bowling,” had been working in New York. No sooner was he transferred back to

Chicago than he came down with the disease.

“If all the bones

of your body ache, and you discover many you did not know you had and they also

ache, you have the Spanish influenza,” Thompson wrote. “Get home quickly.

Immediately upon arrival, take a hot and then a cold bath. Open up all the

windows. Bundle up and get in bed. Send for a doctor, and get the best.

“Some say feed

the ,” Thompson went on. “I starved mine. I was back in the office in

three days, and bowled on the fourth. Not very good, but good enough to

convince myself that bowling was good for what ailed me.”

Just as public

morale was hitting rock bottom, the news finally started to turn good. On Oct.

21, scientists announced they had developed an effective vaccine. Shipments of

the vaccine were rushed to all parts of the country. Chicago alone received

100,000 doses, and inoculations quickly began. Within two weeks, the number of

flu deaths plummeted.

Then, three weeks after the vaccinations began — on Nov. 11, 1918 — an armistice was signed in Europe. The conflict that future generations would call World War I was over.

The country began

to rebound. Bowling began to rebound. The shuttered establishments reopened. In

Indianapolis, proprietor Jess Pritchett took out large display ads in the

city’s newspapers, announcing that his Central Bowling Alleys, “the best

ventilated in the state,” were again open for business. In case anyone missed

the fresh-air selling point, the ad further advised the public to “avoid

influenza by indulging in healthy exercise.”

Two major

regional tournaments, the Middle-West and the Atlantic Coast, had been

cancelled because of the flu outbreak and the war. But in St. Paul, the

International Bowling Association event went on as scheduled. In the spring,

the big one — the American Bowling Congress Tournament — rolled out in Toledo

with a record entry of 796 teams.

The Spanish Flu

was gone. More than 50 million people had died worldwide, a greater death toll

than in all the wars of the 20th century put together. The United States alone

suffered 675,000 deaths. Among bowlers, the most prominent victim was Henry

“Heine” Haselhuhn, a one-time ABC champion. And there were all the others,

known only to their family and friends.

Those left behind

dealt with their grief. One of these was a 29-year-old Chicago bricklayer and

150-average bowler named Florian Przedziankowski. In that horrible October of 1918,

he lost both his wife and his mother to the killer flu.

But Florian moved on, as he had to. In 1920, he remarried, and a year later, he had a daughter. That daughter became my mother.

J.R. Schmidt is Bowlers Journal International's resident historian. A compilation of 90 of his past BJI columns and features, "The Bowling Chronicles," is now available on Amazon or Kindle. This edition of his column appeared in the May issue of BJI. To subscribe now for much more of the industry's best coverage of bowling news and incisive instructional tips and analysis, go here: /bowlers-journal-subscriptions/