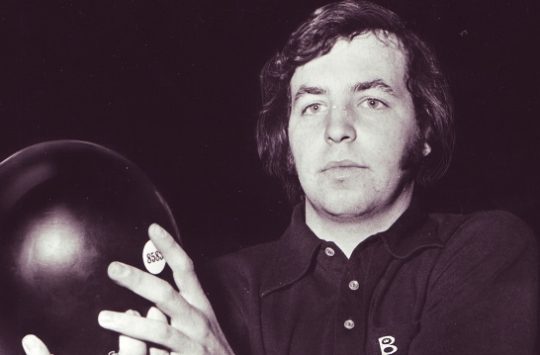

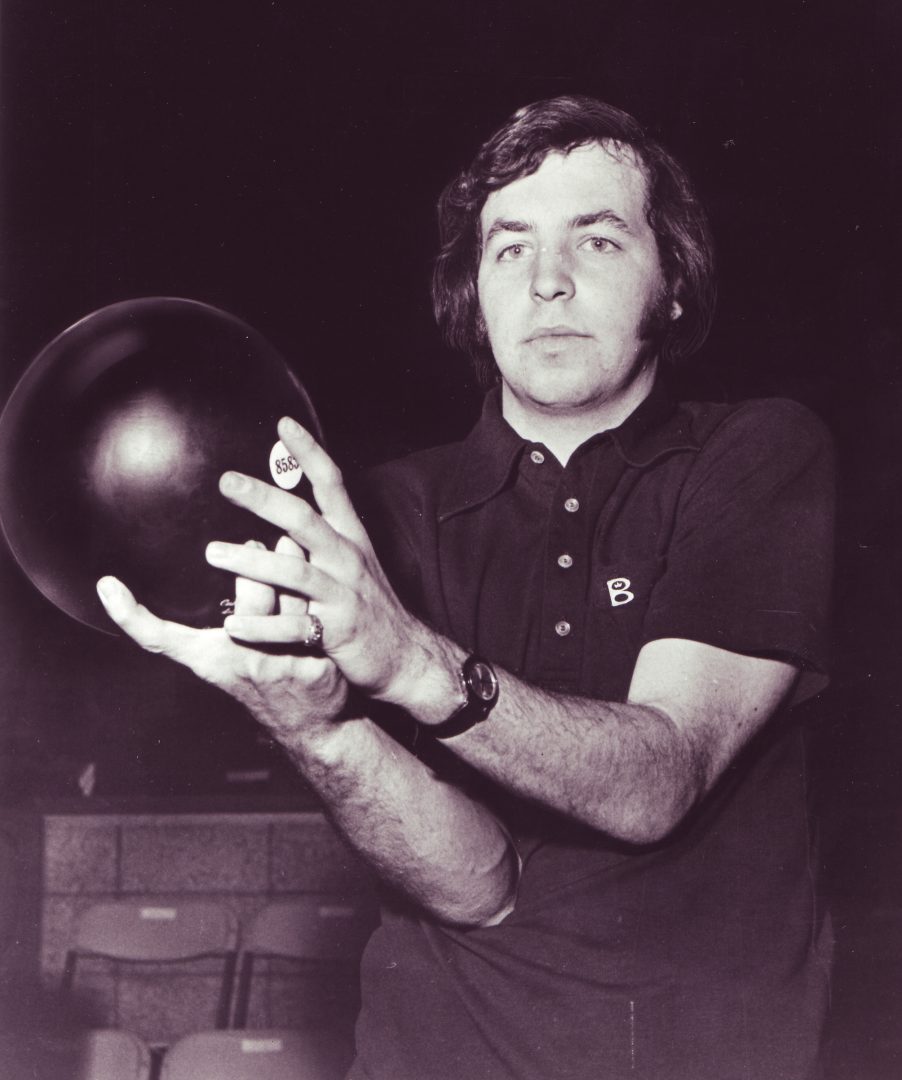

'Just Another Jewish Kid Making a Living': Bowlers Journal's 1979 Profile on Mark Roth

In 1978, Mark Roth, who died Friday at age 70, set a record that still stands today, winning eight titles in a single season and, by the way, piling on another seven the following year for a combined 15 titles in two years. For the below feature that Bowlers Journal ran in its February 1979 issue, Jim Dressel and Lyle Zikes captured Roth at the height of his powers — and the height of his discomfort with the spotlight of fame that talent had cast upon him. We republished that feature in our April 2018 issue, followed by an interview we conducted with Roth in March of 2018. The 34-time PBA Tour champion was in as fine a form for that interview as he was on the lanes when this 1979 story first was published. Check out both, the story and the 2018 interview that follows it, below. . .

BY JIM DRESSEL AND LYLE ZIKES

Superstar! The label fits the man, but the man doesn’t fit the label. Mark Roth just doesn’t think in those terms.

The fame and adulation slip by, ignored as much as possible by its perpetrator. The money is put away or invested as if to pretend that it doesn’t even exist.

“I’m just another Jewish kid making a living,” says the player who just completed the greatest individual season in the history of the Professional Bowlers Association.

The question is — now that he’s shattered every PBA record concerning yearly money earnings and titles, average, consecutive victories, and consecutive cashes and finals — what’s next? In spite of constant speculation that the flame-throwing right-hander will burn out, Roth has been a premier player on the tour for five years now, including the last two in which he was the best. His excellence is not a fluke, nor is he showing any signs of letting up on his winning ways.

Strong and aggressive, he is seen so often on PBA telecasts that the tour should consider making up a voice recording announcing, “… and the winner of that match will go on to meet the tournament leader from North Arlington, N.J.” And on he comes, psyched like a football player. He expects to win and gets mad if he doesn’t.

But behind that terrorizing pin destroyer, few know much about Mark S. Roth. He hasn’t changed much since he was an ambitious young pin chaser at Rainbow Lanes in Brooklyn trying to make good with his bowling ball.

As a teenager, Roth made his pro debut on the 1970 summer tour. Although he made only $1,133 in 14 tournaments that year, few doubted the kid had a lot of raw ability. They said he’d be tremendous if he’d slow down and learn to bowl instead of throw. “Subdue the crank shot a little and develop a stroke,” suggested the men who were beating him. They were still saying that when the 21-year-old mechanic led the Brunswick World Open in 1972 until losing on TV to Don Johnson.

Roth never did anything to try and harness that hook. He just learned to throw harder and turn the ball more. His swing began soaring further over his head and his feet only moved faster. But by 1974 it was clear that he had arrived in spite of it all. He simply was doing things that nobody could do, which has come to mean superiority in the sport.

There are all sorts of ways to describe Roth’s game — herky-jerky, wind up and throw, run and gun — in short, anything the opposite of smooth, refined, and classic. Roth himself has not acquired the polished, urbane demeanor of a superstar. He’d just as soon bowl, win and get back to New York to watch his beloved Rangers.

But being the best requires autographs, interviews, exhibitions and other responsibilities. “I try to bowl and leave,” he says. “I don’t like hanging around too much, but everybody demands so much of your time. When I go home I try to get away for a couple days.”

Or in some cases a few weeks. Besides all his record-breaking achievements in 1978, Roth also set a record for fewest tournaments bowled by a PBA Player of the Year. Roth skipped 10 out of 36 tournaments in 1978, proving it’s the quality rather than the quantity which counts the most. There is some speculation as to how much Roth would win if he took vacations only during tour layoffs.

In the past, Roth was forced to skip tournaments to give his hand and thumb a chance to recuperate from the wear and tear of his release. Although his thumb still occasionally looks like it’s been through a meat grinder, that problem has basically been solved thanks to the work of Bob Simonelli, Mark’s ball driller and advisor. Simonelli’s methods, which include using two drills for the thumb hole, are so tricky and exacting that even the PBA’s renowned ball driller, Larry Lichstein, is reluctant to produce a ball for the Bowler of the Year.

If Roth needs a new ball on the road, he sends word back to Simonelli and the ball is flown in overnight from New York. “It feels so comfortable,” says Mark about the fit. “One time my equipment didn’t come in the right away and I told Larry that I might need a ball to bowl the pro-am. He didn’t want to mess up. He was worried because if my hand rips I’m in trouble.”

The two ingredients which guide his bowling game are simple: instinct and emotion.

“You’ve got to be loose out there,” advises Mark. “That’s my game. Other guys, all they do is think, think, think. The more I think the more trouble I get into. I try to have a good time when I bowl.”

Early in his career, Roth had a poor TV record. He lost his first five games on the tube, averaging under 200 in those attempts. No doubt, the strange, artificial atmosphere had something to do with it. Roth had to learn to let his natural instinctive talent work for him. When he did, it was magic time, as he captured his first career title in Kansas City in 1975 by rolling a 299 in the championship match.

Nobody doubts Roth under pressure anymore. Time after time the past few years he’s needed strikes for big games and he’s come through so repeatedly that he is never counted out unless a 300 won’t help. And once he gets the lead it means the rest of the field will be scrambling for second place. He never chokes.

“I just try to take a deep breath and calm myself down,” says Mark about bowling under pressure. “There are times when you can throw a bad shot. But to have any chance I’ve got to be relaxed and hit the pocket.”

Although Roth has learned he bowls best when he is loose and relaxed, he still gets psyched up to bowl. Always. Whenever he steps up on the approach he has in mind those funny objects at the end of the lane which he intends to demolish. Just knocking them down would be enough for most people, but not for Mark. They’re his personal enemies, and when he rolls a ball at them, he doesn’t intend to take any prisoners.

Respect: Today’s standouts like Bill O’Neill, for whom Mark Roth signed the 2018 Roth-Holman Doubles Championships trophy he won with Jason Belmonte, know who paved the road they took to PBA stardom.

“The biggest kick I get is coming in light and watching the pins bounce all over the place. Blow-outs, wall shots — I like to see the pins go flying across the lane. But I’ll take the solid strikes too.”

On occasion, even the greatest miss. And for Roth, reluctant pins are not something to be taken in stride. Watch the next time he shoots a 10-pin after a solid pocket hit. He’s not just throwing harder to cut down his hook and increase the likelihood of the spare. He’s seeking revenge.

Mark admits he despises solid pocket taps. “When I leave a solid 10 I throw as hard as I can because I just want to kill that pin. I watch to see if the pin bounces around in back and when it does I think, ‘Well I got ya, you turkey.’”

It’s not the most scientific method of spare shooting, but it’s an effective way for Mark to take out his frustrations.

Many folks get the impression that Roth takes his victories for granted. At least it looks that way as “Mock” routinely wins another tournament, goes through with the traditional presentation and necessary interviews and exits the scene in a hurried dash to catch a plane home. He shuns parties because they aren’t his style, neither as guest or host. And he doesn’t celebrate in any of the other more conventional methods. For one thing, he doesn’t drink.

But Roth hardly accepts his championships as a matter of course. “Sometimes I really get crazy,” he shrugs.

HEADER:

Interview: Mark Roth

Early in your tour days critics kept imploring you to change your unorthodox cranker style in favor of a more conventional stroker shot. What gave you the strength to dismiss their criticism and keep developing your way of throwing the ball that nobody had seen before?

Before I went on tour, people said, ‘You’ll never make it. You won’t last three years.’ I was so determined to shut these people up. The same thing happened on tour. They said, ‘You gotta throw it straighter,’ and do this and do that. I was determined to do it my way, and that was it. After ’72, I went home, practiced every day. The place I grew up in (Rainbow Lanes) had four different sides, so it was like a different bowling center every day. I got better and better, and I didn’t care what people thought.

Early in your career, you were convinced that your struggles on tour resulted from your spare game, not from your unorthodox style as people tried to tell you, right?

True. I went out there, and it was a whole different ball game shooting spares. Lane conditions were different, obviously. I wasn’t used to seeing my ball hook at certain spares. And I said, ‘Well, I better learn how to shoot spares again.’ I went home and practiced picking the 10-pin and 7-pin off by itself just to get real accurate throwing it straight. It worked out for me, obviously. Rainbow Lanes was two blocks from my house. I walked there every day and had a locker and kept my stuff there. Every lane was different. Every pair was different. My favorite pair was 7 and 8. On 7, I would play between fourth and fifth arrow; on 8, I would play second arrow. Lanes 5 and 6 were the same as 7 and 8. Lane 6 was a dead track, right between second and third. You could play it right there and the ball just sat in the pocket all day. On 5, you could play anywhere from the gutter to fifth arrow. And 1 and 2 were really brutal, 3 and 4 were pretty good, 11 and 12 were the same as 7 and 8, and 13 and 14 — the end pair — 14 was tight and 13 was third arrow. So, every time I went down to practice I would go to a different pair, but I always wound up back at 7 and 8 to get dead stroke. We had three other sides that were all different — 15 to 28, 29 to 42, and 43 to 56, which hooked the most, but I would go up there and practice anyway. I would still find that the right-hand lanes were tighter than the left-hand lanes because we had the wrong ball returns and everybody shied away from them except me, where I’d crush ‘em.

Right — you’d crush the ball returns with the kick of your trail leg.

Yep. Hit it on the first ball and then the second ball, and I enjoyed it sometimes, getting the frustrations out. I had a lot of partners. A guy who worked in the snack bar, this guy named Phil Marino, we used to practice every day. He was real good, a real good action shooter from Colony Lanes in Brooklyn. We had fun bowling. We bowled for coffee, and soda, and food. He ran the concession, so I’d get a free sandwich and a drink if I beat him. We had lots of fun. We ended up bowling a doubles match together years later and we wound up winning. This guy who owned a men’s store in Brooklyn came down one night. He’d lost $10,000 on a horse. I bowled him singles and I beat him for like two grand. He said, ‘I’m bringing two of my friends in to bowl.’ We said okay. They came in on a Friday night, after the mixed league finished downstairs. I told the girl at the desk to save 7 and 8. She didn’t. We wound up bowling on 11 and 12. I had problems with 12. Philly crushed ‘em. We won like three or four in a row and then we moved to 13 and 14. I shot like 820 something. Night over. We walked out with as couple grand each, and we went out to eat.

Do you think learning to bowl in a place like Rainbow where each pair had its quirks was the reason you were able to win each of those eight titles in a different bowling center in 1978?

Yeah, that’s the big difference. It was all wood houses. It was about which house was more beat up than the other, which house was resurfaced before we go there. I played anywhere from gutter to fourth arrow. At Rainbow, I learned how to play the gutter. I learned how to play everywhere on the lane. That was the advantage of growing up in that house. Four different sides, and they oiled them the same way every day. They oiled them with a spray gun and took a buffer and buffed them out. When you couldn’t hook the ball because they were so stiff, a little oil would come back on the ball and you had to make adjustments. There was one guy I used to watch, this guy Georgie Stillman. Great bowler. He was the only guy who averaged 200 at Rainbow when it was tough. He was a tough action bowler. I learned a lot from him. He used to tuck his pinky. I asked, ‘Why do you do that?’ He goes, ‘I get more turn on the ball.’ So, what do you think I was doing all those years? Tucking my pinky. We would bowl for a buck once in a while, just to make it interesting, but I learned a lot from watching him bowl and watching his attitude, how good he was. Yeah, he was a little cocky, but he was a great bowler.

You set the record in 1978 for the fewest tournaments bowled by a PBA Player of the Year. Why did you skip out on 10 out of the 36 tournaments that season?

I got tired, physically and mentally. Sometimes I just needed to get away.

How many more titles do you think you might have won in 1978 had you bowled more events?

It could have been possible that I might have won another one. But I don’t know what the schedule was. I’d bowl four weeks and take a week off because I was making the finals every week and I just was bowling so much, I needed the break. I was probably bowling a hundred games a week. Easily.

Does it feel crazy to you to think that your 1978 season was 40 years ago now?

Yeah, it does. I remember, I had three wins in a row on the summer tour . I remember the third win was down in Norwalk, California. I was leading the tournament going into Friday. Friday afternoon, I didn’t bowl that well, and the hometown kid, Bobby Fliegman, made a run at me. In position round, he shoots 215. I had to tie him, or win the game, and I win the tournament. They didn’t have TV on the summer tour. I finish on the right lane, and I needed three in a row to tie the match and I had not struck on that lane; I couldn’t hit the pocket that whole game. I threw a triple, dead flush every shot. Tied the match and denied him of winning his first tournament. I shook more after the game was over than when I got up in the 10th frame. Larry was there, and he says, ‘I still can’t believe it.’ I said, ‘I can.’