Marshall Holman: Mt. St. Marshall

The car fire that firefighters squelched outside the HiltonInn Lounge in Akron, Ohio, just up the block from Riviera Lanes where the nextday a 21-year-old Marshall Holman would win the first of his two FirestoneTournament of Champions titles, raised no one from their seats that night.

The car fire that firefighters squelched outside the HiltonInn Lounge in Akron, Ohio, just up the block from Riviera Lanes where the nextday a 21-year-old Marshall Holman would win the first of his two FirestoneTournament of Champions titles, raised no one from their seats that night.

“They had stayed in their seats while the fire departmentextinguished a pretty good car fire in the hotel driveway,” writer Doug Bradfordobserved of the bowling royalty mingling in the lounge.

The figures crowding the lounge after a final round of matchplay that Friday night were characters that defined an irreplaceable era ofprofessional bowling — Billy Hardwick in his “rainbow trousers,” Dick Weberwith his “ice cream suit” and the peroxide-brightened hair that prompted Tourpals to dub him “The Blond Fonz,” Earl Anthony chatting with the Ebonite execswhose contract offer would soften his resistance to “PBA School” in a few years.

If any of them thought back to that driveway fire afterHolman sealed his historic win at the 1976 Firestone Tournament of Championsand considered it a sign of things to come, they would quickly find that theywere on to something — something the PBA Tour had never seen before.

The fire Holman brought to the lanes the following afternoonwould do more than raise people out of their seats; it would raise hell.

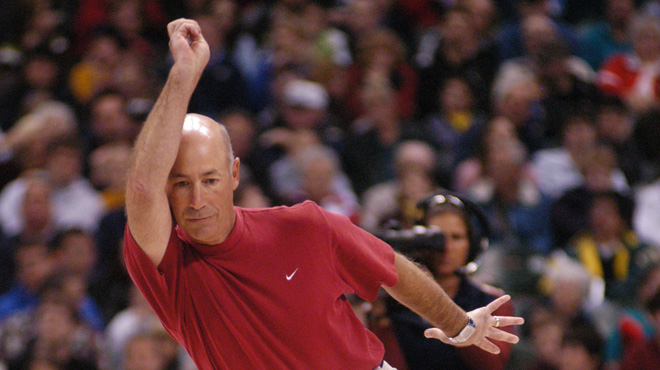

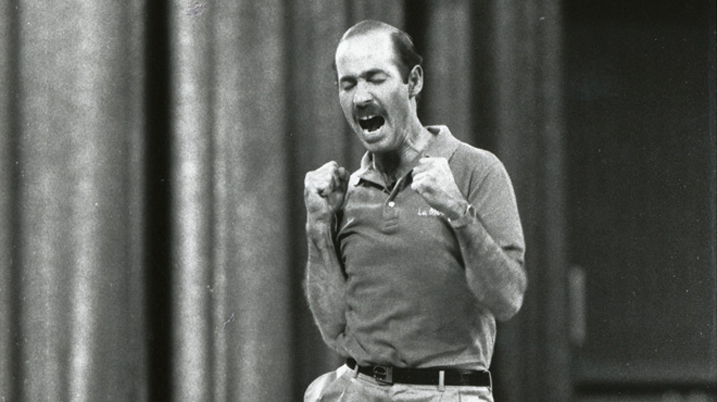

Holman, then with a head of hair so full it looked like alion’s mane, paused at the foul line after a key seventh-frame strike againstHardwick in the Firestone title match. He scowled at the pins with a toothygrimace, pumping his clenched fist three times before turning to take his seatagain.

Chris Schenkel and Bo Burton shared a vaguely nervous laughfrom the booth, and the cocky kid from Medford, Ore., was well on his way tobecoming the man called “Mount St. Marshall.”

Holman and his gritted teeth amassed many monikers from thatday on: “The Medford Maniac,” “The Medford Meteor,” “rum raisin in a world ofvanilla,” “the compact little cannon.”

In a 1982 Bowlers Journal profile, Holman himself preferredto be known as “a Jaguar in a world of Volkswagens.”

“Bowling is like cottage cheese,” he said in anotherinterview. “It can be kind of bland. Well, I’m the salt and pepper that makesit more palatable.”

Those are the words of the Marshall Holman who rarelystruggled to afford himself the approval his critics withheld, critics whomistook that brash exterior for the man himself when in fact it was merely thecloak that disguised the frightened boy inside him.

“I’m very confident,” Holman said as Bo Burton asked him ifhe was nervous in advance of his Firestone title match against Billy Hardwick.“I’ve got a good shot on the TV pair, and I think I can win.”

That was some pretty big talk for a kid who had just becomeeligible for the Firestone only months earlier. Then again, that “kid” hadrecently decimated PBA and USBC Hall of Famer Carmen Salvino, 270-213, to winhis second title before he was old enough to spend a dime of his prize check ona beer at the bar that afternoon.

These days, the “other” Marshall Holman, the one who runs atax service in Oregon and looks back at the 22 titles he gathered on Tour asthe life of a man he no longer knows, more readily fesses up to the artificebehind the machismo.

“It was a defense mechanism,” Holman says. “I was young, andI was still pretty new to the game. It was my way of not letting my competitorsknow that I was nervous. But it was unbridled, in-your-face enthusiasm, andpeople hadn’t seen much of that on tour at the time so they were taken aback byit.”

Back in 1982, fresh on the heels of his first of two U.S.Open titles (1981, 1985), Holman shed some light on the man behind the volcano.

“People think I’m cocky but cockiness is my shield againstthe hurts out there,” Holman explained at the time.

If coverage throughout the bowling media was any indication,though, not many people were buying the psychoanalysis he had to sell.

“I suspect that when Marshall first tumbled from his crib,he muttered ‘Well, no more Mr. Nice Guy!’” John Archibald quipped in a BowlersJournal story that same year.

In the aftermath of the PBA’s 10-week suspension of Holmanafter he kicked out a foul light on live TV at the 1980 PBA Doubles Classic inLas Vegas, though, even Holman could not have expected to find many sympatheticears within the bowling community.

“A man has to hesitate before pleading on behalf of MarshallHolman,” Archibald continued. “You begin to think how the public defenderassigned to Attila the Hun would have felt.”

“When the pin gods aren’t cooperating, neither is Holman,”Dan Herbst wrote in Bowlers Journal. “Let him perceive the smallest soundsduring a bad shot and he’ll look in the direction of the culprit and scratchhis forehead using all but the four outside fingers.”

Holman may have come off as a “maniac” to many as he punchedat the air and seethed, but one man who saw the worth in Holman’s penchant forshowmanship was the master showman himself, the man whom Holman grew upidolizing: Salvino.

“I’d rather have one Marshall Holman to any 10 of the robotswe have out there,” Salvino said of Holman’s place on the PBA Tour in 1982.

Showman or not, today Holman takes a different view of theman he was in his former life.

“It’s like that Sinatra song, ‘Regrets, I’ve had a few, butthen again, too few to mention,’” Holman says from his Medford home. “Well,there’s more than a few for me. I was just young and immature. Obscene gesturestoward the pins, confrontations with fans. They would say something derogatoryto me and I’d stare them down or respond rudely to them.

“I don’t know how I made it through all those years on Tourwithout getting in some physical confrontation.”

If “Mount St. Marshall” put on the airs of a fighter on thelanes, he is the first to admit that reality paints quite a different picture.

“Even though when I was on the lanes I probably looked likeI was a pretty good fighter, I have a perfect record in fights in my lifetime,the last one being in seventh grade. I stand at a perfect No Wins and ThreeLosses,” he jokes.

One record that stands far from perfect is the TV recordHolman recorded in his career, at one point losing 19 of 21 TV matches and, bythe time he appeared on the 1985 U.S. Open telecast, winning just six of hislast 20 appearances as the top seed.

But win or lose, hero or villain, Marshall Holman alwaysdelivered the show that fans expected and just as they had done so many timesbefore tuned in for another episode of “The Medford Maniac.”

“Can you believe it? People have come up to me and told methey think I’m disgusting, that they’d rather watch someone just go up andthrow the ball and then sit down,” a 25-year-old Holman wrote in a story titled“Why I Act the Way I Do.” “Sure. And they like to watch the test pattern ontheir TV sets, too.”

Holman’s perceived “cockiness” might well have been hisstrongest defense against “all the hurts out there,” but clearly it alsooriginated from a keen sense of show business.

But that is how it is when you’re the son of a man who spentdecades in show business himself. Phil Holman, who took meticulous notes on hisson Marshall’s television work for ESPN in the 1990s and shared hisobservations after each telecast — “my father passed away in 2001, and I stillhave those notes,” Holman says — proved to be no shabby showman himself the dayhe sat atop a San Francisco flagpole to do his radio show in 1953, a feat forwhich he earned national exposure and the nickname “Holman the Poleman.”

Phil Holman worked at KOBI-TV in Medford among other outletsbefore turning to a career in advertising.

“Larry Lichstein used to call me ‘Holman the Bowlman’because of my father’s nickname,” Holman recalls.

“My father would take over the intercom at Safeway and doone of his routines,” Holman told the Medford Mail Tribune shortly after hisfather succumbed to cancer in 2001. “I’d say ‘Dad, we only came for a quart ofmilk.’”

According to a 1976 story by then-Editor-in-Chief of BowlersJournal Jim Dressel, Phil Holman “became the world’s first flagpole-sittingdisc jockey.”

How fitting it is, then, that the man whose obscureeccentricities carved their minor niche in American history is also the manwhose son made plenty of history himself, a son whose name will be foreverenshrined in bowling lore when the United States Bowling Congress officiallyinducts Marshall Holman into the USBC Hall of Fame on May 12, 2010.