On Earl Anthony's Birthday, Hear from His Biographer Barry Sparks

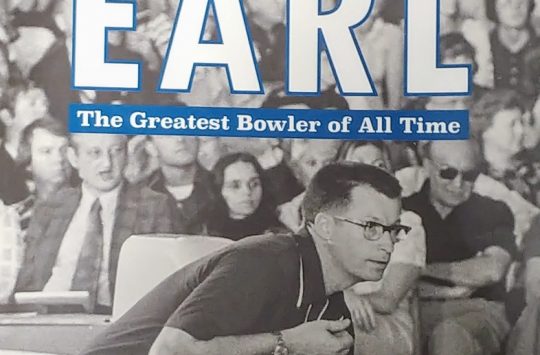

As today marks what would have been 43-time PBA Tour champion Earl Anthony's 82nd birthday and you're probably spending yet another day at home as the world waits out the COVID-19 pandemic, we've got the perfect prescriptions for your cabin fever: Our in-depth interview with Anthony's biographer, Barry Sparks, and his new biography of Anthony, "Earl: The Greatest Bowler of All Time," is available at EarlAnthonyBook.com.

Here is our conversation with Sparks. When you're done, why not pick up a copy of the book? It offers an incredibly well-researched look at the career of one of the sport's greatest champions, based on interviews with more than 100 people--including 23 PBA Hall of Famers.

Congratulations on the publication of this book and on the quality of the project. It is an outstanding achievement.

I appreciate that and I agree that Luby Publishing did a great job with the book. It looks fantastic, the photos are great, and it's something that I'm proud of and I'm pretty sure Keith Hamilton is proud of. That's great.

What interested you in writing Earl Anthony's biography?

One day, I was making a list of some book ideas, and I realized there was no biography of Earl, and I thought, 'Boy, how strange, and what an injustice.' You could name any sport and ask anyone who are the greatest athletes in that sport, and there would be a biography of each one of the people they name, and there would probably be at least two or three biographies of at least one of them. But, in bowling, that wasn't true. Earl Anthony, there was no biography whatsoever, and really there's been no biography of a PBA bowler. Carmen Salvino worked with a guy from the Wall Street Journal to do a book on bowling that was a little bit on Carmen, a little bit instruction, but it wasn't strictly a biography. So I thought, 'Hey, that's something that I think I can rectify.'

You spoke with 110 sources, including 23 PBA Hall of Famers. What did you learn about Earl that you didn't already know?

I knew a little bit about Earl when I started writing this book. I knew who he was, what his record was, things like that. But there was a lot I didn't know. I didn't realize that Earl had a heart attack at age 40, and that he won three Player of the Year awards before he had the heart attack and then he came back and won three more. It was just amazing that any athlete in any sport would suffer a heart attack and come back not only to a competitive level but come back to be named Player of the Year. Eddie Elias, the founder of the PBA, said Earl's story was one of the greatest comeback stories in sports. I couldn't agree more, but it wasn't that well-publicized in the general media.

You note in the book that Earl was called an "anonymous superstar," but you also note that 20 million people a week were tuning in to watch him on ABC's Pro Bowlers' Tour. So how was it that he was "anonymous" when he had an audience of 20 million people?

That's a good point. The thing was that he didn't transcend the sport, whereas, at the same time, athletes like Jimmy Connors and Arnold Palmer transcended their sports. They drew people to tennis and golf who didn't necessarily play tennis or golf, but they watched tennis and golf on TV because they were attracted to the personalities and the competition. Earl didn't get beyond the true bowling fans. There were a lot of them. There were nine million league bowlers at that time. Beyond that, people might have known his name, but not generally.

Which brings us to Earl's character, because you mention also that he wasn't necessarily as charismatic as top athletes in other sports.

He was an introvert, but he recognized his responsibility to bowling. He became the go-to guy for the media. He did lots of media interviews. He was fantastic with fans. He never turned down an autograph. He took his time with them. This was all counter to his nature, and not all athletes make that change. They leave it up to somebody else or say, 'That's not my job' or they are uncomfortable doing it. Earl was uncomfortable doing it but he still did it. He actually practiced how to make people more comfortable; he knew some people were intimidated to ask him for an autograph, and he worked at putting them at ease. Gary Mage, one of his best friends on tour, said that Earl may not have been Arnold Palmer when he first went out there, but he was at the end.

As impressive as it was that Earl won 15 titles across three seasons in the 1970s, Mark Roth comes along and wins 15 titles across just two seasons in 1978 and ’79. What can you tell me about the rivalry that existed between the two when Mark Roth caught fire towards the end of that decade?

Mark and Earl bowled in the championship match five times. In fact, it surprised me that it was only five times considering they were the top two bowlers out there, with maybe throwing Marshall Holman in there. When Mark was coming along in ’77, ’78 and ’79, there’s a part in the book where he says, ‘Earl Can’t be number one forever. No one can.’ Mark was the up-and-comer and everybody knew that. I don’t know how much of a rivalry they had. I know they were both very, very competitive and had very different styles and different personalities. In ’79, that was the year Earl finished as the number-one seed seven times and ended up being second six times. That was a subpar year for Earl, in a sense. It was a good year for anybody else. But, in ’78 Earl has his heart attack and in ’79, Earl has his comeback tour. So, really, maybe Earl wasn’t at his best then, but Earl was also a little older than everybody else out on the tour, so Mark had the advantage of youth and being the up-and-comer.

Tell me about the number of years Earl eclipsed the six-figure mark in earnings and the significance of that aspect of Earl’s sterling career on tour.

Well, it was a big deal for a bowler to go over $100,000 a year; it wasn’t necessarily a big deal in the sports world because $100,000, by ’79 or ’81, had been reached by a lot of athletes. I think by then there were 32 golfers who reached $100,000 a year. Earl felt, and a lot of other people felt, that it brought a lot of attention to the PBA that people would see you could make some money on the PBA Tour and a lot of kids who were watching it would aspire to go out on the PBA Tour. He thought he might get more sponsors and there would be some influx of money, which, really, it wasn’t that much for him. If he had been a tennis player, it certainly would have been more lucrative. So, it did elevate the sport when he went over $100,000. Now, you have to remember that Earl had to subtract his expenses. There was one year that Earl made $164,000, which was a record at the time in the PBA. That was equivalent to the highest paid place kicker in the NFL, but that place kicker didn’t have to pay expenses. So that amount of income was a little skewed by having to pay his expenses.

What compelled Earl to retire in 1984?

Well, by then he was really pushing it because he had long lost his desire to be out on tour. He was out there for 14 years and it took a lot out of him mentally and physically. He was hoping at times that he would catch a spark and he would feel like bowling again and start practicing again, but he never did. He’d say that when he went home he would miss the competition, but as soon as he went back out on the road, after just one day he wanted to go home. He had a contract with Ebonite to bowl in at least 20 tournaments, so he was obliged to do that. At one point, Earl struggled in a match in the stepladder finals of the Waukegan Open, and he was bowling Les Zikes — I think it might have been in the semifinals; it wasn’t in the championship match — but Earl bowled a 150. That was just unheard of for Earl. And really, it was kind of clear to him that the desire was gone, and actually back in ’76, he was only going to bowl a couple more years, but when he had the heart attack, that changed everything, while that same year he went through the divorce with his wife and Earl didn’t have much money after the divorce. He gave everything to his wife except his car and $10,000, so he had to start over. He needed the money, and that kept him out there, but probably he stayed a little longer than he should have … He had to talk to Ebonite to let him out of the contract so he could retire, and they were gracious enough to do it, and that was a big relief to Earl.