Spare a Life

November 30, 2024

Sometimes, the smallest gesture can pay the biggest dividends. The most innocuous items can have the most consequential impact. The mere germ of an idea can be the thing that saves a life.

An interaction Jessica Overton had with Dan Griner at one of the latter’s two pro shops — Xtreme Performance Pro Shop, which has locations in Hampton and Williamsburg, Virginia — offers a case in point.

“It all started when I literally walked up to Dan Griner’s pro shop, and he had mocked up some shammies,” Overton says. “I was like, ‘Oh! Is this for a cause?’ He said, ‘Yes!’ I said, ‘I want that shammy.’”

With the help of Griner’s graphic-designer daughter Judia, the shammies were emblazoned with the logo of an organization Griner then was just on the verge of launching. Officially launched in January of this year, the group is called “Strike Against Suicide, Spare a Life.” It gives away to active military personnel and military veterans materials intended to coax them into the bowling center for the first time or prolong their existing bowling careers — balls, shoes, shammies, ball cleaner — products the organization also sells to raise money for its cause.

In the majority of cases, the bowling center is a better place than the one they occupy when that shammy, or bottle of ball cleaner, or pair of shoes comes their way. Chiefly, their minds, that isolated place determined to take them down the dark roads of self-destructive thoughts and impulses. It is a place where anything is possible, one they too often occupy alone in the isolation of the barracks, ships or homes. It is a place Overton knows all too well.

“A few years ago, I dealt with some battles with depression, and bowling was my outlet,” says Overton, an educator with the Norfolk, Virginia, public school system who serves the organization in the capacity of secretary and treasurer. “That was how I let go of negative energy. Bowling was something, at that point in my life, that I felt like I could control. I had a lot of things going on in my life, but bowling was something I had a handle on. It was something I loved to do.”

It has been that way for Overton for a very long time.

The 34-year-old “grew up in the bowling alley, pretty much. You could go to Mechanicsville, Virginia, and there are probably hundreds of people there who have seen me run around a bowling alley in a diaper,” she chuckles.

At the time of that chance meeting Overton had with Griner decades later, Overton says, Strike Against Suicide “wasn’t even fully formed yet, and when Dan and Ashley [Scott] asked me to jump on board, it wasn’t even a hesitation.”

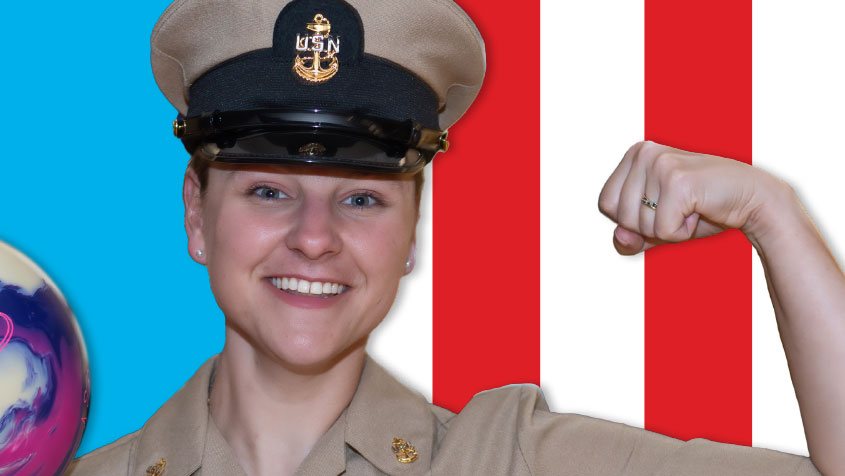

Scott, too, formed some of her life’s earliest memories in a bowling center. Now 35, the Navy Chief Petty Officer has “been around bowling since I was two weeks old. My family is a bowling family. My mom worked at the control counter and my dad was a mechanic. So, from a very early age, I was surrounded by bowling. I just grew up like most [youth bowlers] now, bowling Saturday-morning youth leagues. I didn’t compete at the level some youth bowlers do now, because we just didn’t have the means to do things like that, So I just stuck with Saturday youth league all the way up through high school.”

While the Ohio-born Scott has been surrounded by bowling from the time she too was in diapers at a place then called Cloverleaf Lanes in Independence — a town name boasting no small dose of coincidence for someone fated to pursue a military career — these days, as she serves her country in uniform while bowling for the Navy bowling team, she is surrounded by something else: a darkness she hopes bowling can repel.

“Dan Griner, who recently retired (in July 2023) after 30 years with the Marine Core, was telling us about his vision [for Strike Against Suicide], and it really hit home for people like myself and Dan Hawk (her boyfriend, who served the Navy for 22 years before his 2008 retirement). We have lost shipmates to suicide. I have lost shipmates who worked in the same office as I did — shipmates whom I helped with their careers, people with whom I’ve become more than just shipmates and friends,” Scott explains.

“We knew there was a need and we wanted to see what we could do to help combat that. If we have just kept one sailor, soldier, airman or Marine alive for one more day through recreation and bowling, then I know the vision is working.”

Scott has signed on as the organization’s Vice President, and Griner swears by her importance to his cause.

“She’s a good bowler, she’s always been part of the sport, she’s always competing, so when I had the chance to get with her, I said, ‘Why don’t you just hop on board and get with me at Strike Against Suicide?’ and she was all for it,” says Griner, 48. “She’s been my right hand behind the whole process. She’s the Vice President of it, and sometimes I feel guilty about over-tasking her. I put a lot on her plate, because she’s still active duty and she’s got other things she’s doing, but she always manages to get them done. It’s that old saying in the military, when you’re good at what you do, you don’t get breaks; you get more thrown at you.”

At the same time, Griner advises that his cause is not about any single individual, and cautions that the mission will have failed if any one person becomes its backbone. The idea of serving a cause bigger than herself, which entails an awareness that others’ needs will come before hers at least at times, is no hard idea to fathom for someone of Scott’s background.

“I’m the last of eight kids,” she says matter-of-factly in her deadpan manner of speaking. “There were, at one point, four of us who bowled. Two of my brothers, myself, and my sister, but now it’s just myself and my sister who bowl.”

What was it like growing up in a household that included so many children? Simple.

“Chaos,” Scott says, chuckling.

It’s Personal

In an environment like that, you learn quickly that it’s not about you. And her efforts with Strike Against Suicide most certainly are not about her but about those the cause urgently seeks to reach. It is about people like her buddy Ron Condrey, whose story forever will charge her efforts for Strike Against Suicide with an incorrigible drive and commitment.

“When I was just a junior sailor, he was a Chief. I was his retirement clerk. I would work closely with [those nearing retirement] to make sure all of their paperwork was good for retirement, so we spent a lot of time working together and we ended up becoming really good friends, but Ron had spent multiple tours overseas and he was blown up a couple of times, so you could see the battle wounds on his arms and his legs.

“I remember being at the psych ward with him, helping him with his retirement stuff. You only retire once, so you want to get it right. Being around that and forming a great friendship with him, it was a beautiful thing. But he just had those demons and so much going on that he lost his battle with his demons and took his own life, and his wife is an amazing person, the mayor of a small town, and she keeps his memory living on by advocating for mental health. He is one person who has impacted me a lot because you don’t know what suicide looks like. That can look like someone smiling or it could look like someone crying. You would never be able to tell.”

If you hear a certain eloquence in Scott’s speech, you are not alone.

Brad Edelman, whose High Roller, Inc., organization runs the Military Bowling Championships twice each year, provides her with a table, booth space, and a platform during the event’s opening ceremonies to speak on Strike Against Suicide’s behalf.

“She loves speaking in front of people and she is very good at it,” Edelman observes.

Scott also has put in several recent appearances on Phantom Radio to talk up the organization and, along with Griner, continually seeks opportunities to broaden awareness of it.

Overton, drawn to the cause by personal experience despite not herself serving in the military, sees first-hand that Griner’s vision for his organization, driven home by the likes of Scott and others including herself, is working.

“I am seeing veterans come [into the bowling center] with smiles on their faces when they didn’t have smiles before,” she says. “There are veterans who come into the bowling alley and want to bowl but they don’t have shoes, or they don’t want to pay the $10 for shoes every time they come bowling, but they want to learn the sport, they want to be involved with the bowling community, so I think Strike Against Suicide, Spare a Life is giving prospective bowlers and current bowlers an outlet so they can continue, or become, a member of that community.”

That word “community” comes up in every conversation with anyone involved with the organization’s efforts.

For Hawk, 56, who lost his 34-year-old son Derrick to an apparent suicide earlier this year, the reason for that comes down to a basic human yearning for connection.

“The goal is to get them out of the house, or the barracks, or off the ship, and get them interacting with people,” he says of the organization’s appeal to veterans or those still on active duty. “Bowling is our common thread among the group. We all love bowling. We know that there is a bowling community that really gives a damn about people out there, and we’re a part of it.”

Hawk, who provides his project-management expertise to the organization while also handling shipping and receiving, knows firsthand just how widespread that community is. He sees the orders for those shammies and bottles of ball cleaner come in to support the organization’s cause. They come from everywhere.

“We see it across the nation and all over the world,” Hawk says. “All the way over to Idaho, down into California and Texas, in Japan, Hawaii, people are buying stuff and the word is getting out about what we’re doing. It’s just a matter of getting people to realize that there are people who give a damn about them, and we’re trying to get the bowling community to realize that we can help people, and it doesn’t take much.”

Hawk, who followed older brother John into the Navy in 1986 at age 17 and retired in 2008, is as familiar with the bowling community as anyone.

“My dad got us bowling,” he explains. “We moved from Ohio to Tampa, Florida, when I was about 10 years old, and he was a bowler down there. Tommy Crites was the PBA Rookie of the Year in 1985, and he was Tommy’s coach in high school. We kind of grew up with Tommy Crites; he was a generation ahead of us, so he helped coach us when we were kids and I stopped when I was in high school. But, once I joined the military, transferring all the time and going from ship to ship, plus having a young family, I wasn’t able to keep up with it.”

He picked up bowling again around 2004 as he neared retirement, and today carries a 225 average.

Like the military personnel both past and present he hopes Strike Against Suicide impacts, bowling was, at that time in Hawk’s life, “just something to get me out of the house.”

Scott, who has bowled for the Navy for 13 years now and has a 300 game and an 800 series to her credit, knows well the power behind bowling’s ability to just get people out of the house.

“We aim to get sailors, soldiers, airmen and Marines out of their house, barracks and ships because that’s where you spend a lot of time alone. You’re alone with your thoughts. And sometimes, that is not good. What we want to do is create a safe environment where these service members can get out of those [isolating] locations and join other service members and destress, recalibrate, and be around like-minded individuals.”

That point about like-minded individuals is especially resonant for members of the unique cadre that military personnel comprise.

“It’s easier to have conversations about what we’re going through with other military members who can relate,” Scott explains. “That’s not to say that some civilians can’t relate, but they don’t know what they don’t know. They can only imagine. They can only sympathize.

“But those sailors, those people who have been going through it, they’ve been on the same deployment, they’ve been out to sea for any number of months, they’ve been stationed overseas away from their families, so we just aim to get them out of the house and around like-minded individuals and support their mental health through recreation. We do that by paying for their time on the lanes, giving them bowling balls to start their bowling journey, or bowling shoes, ball cleaner, swag, all those things that will help them use recreation as a form of mental-health treatment.”

Stigma

If there is a stigma attached to depression or suicidal ideation among the general public, that stigma intensifies exponentially among those in uniform.

As Jay Miller, a scratch bowler now in his 15th year with the Navy, explains, “In the military, you’re held to a higher standard. And sometimes, when you’re held to a higher standard, it could be a little frightening to have these thoughts and worry that people are going to think that you’re weak because of that. You worry that people are going to think less of you. So, they tend to keep those feelings bottled up because they don’t want people to feel that way about them.

“But we want people to know that they’re not going to be judged just because they’re having those thoughts. We’re here to help you know that those thoughts are valid and know why they are important and why it is important that they are here.”

Miller serves Strike Against Suicide as a promotion advisor, finding ways to get the word out about the organization and what it does.

“My goal is to reach as many people as I can with my networking and my military experience and just talk to individuals to help them understand that they are not alone,” he says.

Hawk, too, is all too familiar with the reasons military service members often are more given to bottling up their darker thoughts than they are to voice them or even display the slightest outward evidence of the turmoil within themselves.

“The military trains us to basically be emotionless,” he says. “We need to be able to do things [that require a certain stoicism], and we might be feeling something on the inside, but let’s not show that on the outside. In some societies, and in parts of our own society, that’s perceived to be part of being ‘a man,’ or part of being ‘an adult.’

“But the reality is that we become experts at hiding what’s going on inside. So, we’ve got to be able to let people know, we’ve got to reach out to them and draw those feelings out so that we can discuss them and put them to bed.

“I myself have been unsuccessful at doing that more times than I want, with friends and even with my son, who suffered with depression and had suicidal ideation many times in his adult life. I wasn’t able to get him away from the demons in his head.

“It’s the same thing with [Ron Condrey]. He sought treatment but it didn’t cure what was going on inside of his head because of several traumatic brain injuries he suffered, and eventually he lost his battle.

“So, we’ve got to be able to get these people to talk. Like Ashley says, if we save one, it doesn’t matter how much time we spend trying to do that. If we save one, it will be worth it, because that one person isn’t finished with what they’re set out to do on this Earth. They’re not done. We’ve got to make sure that they realize that.”

Scott, too, understands what a tall order that can be among military service members.

“In the military, you’re supposed to be so tough, right? We’re training war fighters. You’re supposed to be bad to the bone. And when someone in the military is going through those things, they’re not going to talk about it and they’re not going to seek help because it exposes them to the perception that they are weak.

“And war fighters aren’t weak. We don’t win wars by being weak, right? So, they would rather not say anything and not talk about it because of perceptions about what they are supposed to be.”

It is clear that such an approach to managing their demons is not working. In the first three months of 2024, suicide claimed the lives of 94 active service members, 24 reserve members, and 21 serving in the National Guard. Yet, even had some of them sought help, it might not necessarily have been readily available, and this is another problem Scott identifies as a reason for the scourge suicide has become throughout the military.

There is, Scott explains, a “lack of military treatment facilities, and a lack of qualified people to provide treatment, like doctors. When something as simple as getting my eyes checked is booked three months out, can you imagine someone really needing a mental-health appointment and being told it will be five months? Well, guess what? That person might not be around in five months. There are service members who are going out into the civilian sector and paying out of pocket for mental-health treatment because we are so backlogged and there are not enough providers to handle the amount of sailors who are looking to get help.”

Military Bowling Championships

One event held twice annually — each January and again each August — provides some degree of help, however small, to those looking to capture a piece of that bowling community which, as Hawk says, gives a damn about them. That event is the Military Bowling Championships, and it amplifies and embodies Strike Against Suicide’s mission to use bowling as a gathering point around which service members can enjoy the healing benefits of social interaction with people of similar backgrounds and life experience.

Brad Edelman, whose High Roller, Inc., organization took over the event in 2005 following the closure of its host The Castaways (formerly The Showboat) in Las Vegas, saw more than 6,200 bowlers shoe up for his August event at South Point in Las Vegas, which, unlike the January edition, does allow non-military “guests” to mix in with the active and veteran service members who bowl.

“We have grown it, and the one in January is now known as the largest participation of military personnel in a sporting event in the world, and we were told that by the Department of Defense,” says Edelman, who calls the experience of running his Military Bowling Championships “humbling.”

He explains that, at any given Military bowling Championships tournament, “You never know who you’re speaking to. Somebody will come up to you in shorts and a t-shirt ready to bowl, and in a previous life he was a three-star somewhere.

“We’ve met people who openly will tell you they’ve killed 300 people, and somebody else will say he was in a troop where half his troop was killed. The things you hear and the people you meet, it makes you really think about the phrase, ‘Thank you for your service.’ Well, until you realize what that service actually is, it’s just mind-boggling.”

Edelman explains that his participants, by and large, do not even come to the event for the bowling but rather for the very benefits Strike Against Suicide attributes to the sport. Hawk, for his part, is one such example.

“I’ll tell you this: I am a scratch bowler, and the August tournament is a handicap tournament. Unless I’m shooting 900, there’s no way I’m going to win that tournament. That’s not my purpose for going. My purpose for going is to see the people that I’ve served with, fellow bowlers that I have served with previously, and meet new ones. There’s always somebody out there with a story to tell, and it is so prevalent,” he says.

“When Ashley and I were out there raising money by selling merchandise this past August, we had people come up to us and tell us stories. One guy said that on that date a few years ago, he sat down on the couch in his front room and was about to [take his own life] when he looked up and saw Christmas lights across the street and he stopped what he was doing because he remembered that his granddaughters just love Christmas.”

Would a civilian understand that story as deeply as a military service member?

“I’m sure they could on some level,” says Hawk, “but would someone who was a non-veteran walk up to that merchandise table and tell you that story? Chances are that they would not, because they’re not going to get that personal with you. You don’t have that type of connection with them. The military connection isn’t something that can be related to. You can’t say, ‘Oh yeah, we went on vacation for two weeks and we have this connection just like they do in the military.’ Absolutely not. These veterans fought for each other just to stay alive.”

Which is the very connection and community that events like the Military Bowling Championships harness.

Miller says the tournament “gives us a chance to see military people that we don’t get to see everyday. It gives a chance for all of us — active duty, reserve, retired or just veterans — to come back and reconnect and have fun doing it. And it’s in Vegas, so you’re also getting the chance to experience that lifestyle as well with the people you might have gone to war with or were on deployment with.”

And the age range the participants comprise each year is almost incomprehensibly vast. The most recent January tournament, Edelman reports, included eighteen bowlers who were at least 90 years old. It was the 68th annual Military Bowling Championships, which began at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas.

Overton hopes that someday soon Strike Against Suicide’s reach also can include children of military veterans, as the educator within the Norfolk, Virginia, public school system says that is a place “where the military population is very high, and I see a lot of students struggle with a parent being deployed and missing them, so I feel as though this organization can help that, too. If nothing else, it can provide those children an outlet.”

Griner’s vision includes a day when his organization can pay for veterans’ lineage at bowling centers, because, as he puts it, “In return for that, I get these guys and gals to get out, socialize, bowl, have that interaction, and that could mean the difference between that and sitting at home, drinking a fifth of whiskey, tying a rope around their neck and hanging themselves. Small things make a difference.”

In the meantime, Miller is emphatic in his hope that the organization’s efforts will make a positive impact on suicide rates among military service people.

“I wouldn’t be a part of this organization if I didn’t believe it could help in some way,” he says. “I believe that there is a path forward for the numbers of suicides in the military to go down, and I think Strike Against Suicide is on the right path. I’ve witnessed first-hand sailors who have had suicidal thoughts and, because they decided to branch out and believe in the organization, now they are on the other end of it. And now, they’re talking to other sailors, soldiers and airmen about their experiences.”

As Overton puts it, “I’ve had conversations with some outside the bowling alley who have told me that if it weren’t for bowling, having somewhere to go and experience that community and take out some frustration on the lanes, they don’t know if they would be here.”

Everyone working with Striking Against Suicide, Spare a Life is elated that they are still here, and wants those on the brink to know that they, too, have an unfinished purpose to pursue in this world.

Those interested in learning more or helping the cause can go to strikeagainstsuicide.com to do so.

An interaction Jessica Overton had with Dan Griner at one of the latter’s two pro shops — Xtreme Performance Pro Shop, which has locations in Hampton and Williamsburg, Virginia — offers a case in point.

“It all started when I literally walked up to Dan Griner’s pro shop, and he had mocked up some shammies,” Overton says. “I was like, ‘Oh! Is this for a cause?’ He said, ‘Yes!’ I said, ‘I want that shammy.’”

With the help of Griner’s graphic-designer daughter Judia, the shammies were emblazoned with the logo of an organization Griner then was just on the verge of launching. Officially launched in January of this year, the group is called “Strike Against Suicide, Spare a Life.” It gives away to active military personnel and military veterans materials intended to coax them into the bowling center for the first time or prolong their existing bowling careers — balls, shoes, shammies, ball cleaner — products the organization also sells to raise money for its cause.

In the majority of cases, the bowling center is a better place than the one they occupy when that shammy, or bottle of ball cleaner, or pair of shoes comes their way. Chiefly, their minds, that isolated place determined to take them down the dark roads of self-destructive thoughts and impulses. It is a place where anything is possible, one they too often occupy alone in the isolation of the barracks, ships or homes. It is a place Overton knows all too well.

“A few years ago, I dealt with some battles with depression, and bowling was my outlet,” says Overton, an educator with the Norfolk, Virginia, public school system who serves the organization in the capacity of secretary and treasurer. “That was how I let go of negative energy. Bowling was something, at that point in my life, that I felt like I could control. I had a lot of things going on in my life, but bowling was something I had a handle on. It was something I loved to do.”

It has been that way for Overton for a very long time.

The 34-year-old “grew up in the bowling alley, pretty much. You could go to Mechanicsville, Virginia, and there are probably hundreds of people there who have seen me run around a bowling alley in a diaper,” she chuckles.

At the time of that chance meeting Overton had with Griner decades later, Overton says, Strike Against Suicide “wasn’t even fully formed yet, and when Dan and Ashley [Scott] asked me to jump on board, it wasn’t even a hesitation.”

Scott, too, formed some of her life’s earliest memories in a bowling center. Now 35, the Navy Chief Petty Officer has “been around bowling since I was two weeks old. My family is a bowling family. My mom worked at the control counter and my dad was a mechanic. So, from a very early age, I was surrounded by bowling. I just grew up like most [youth bowlers] now, bowling Saturday-morning youth leagues. I didn’t compete at the level some youth bowlers do now, because we just didn’t have the means to do things like that, So I just stuck with Saturday youth league all the way up through high school.”

While the Ohio-born Scott has been surrounded by bowling from the time she too was in diapers at a place then called Cloverleaf Lanes in Independence — a town name boasting no small dose of coincidence for someone fated to pursue a military career — these days, as she serves her country in uniform while bowling for the Navy bowling team, she is surrounded by something else: a darkness she hopes bowling can repel.

“Dan Griner, who recently retired (in July 2023) after 30 years with the Marine Core, was telling us about his vision [for Strike Against Suicide], and it really hit home for people like myself and Dan Hawk (her boyfriend, who served the Navy for 22 years before his 2008 retirement). We have lost shipmates to suicide. I have lost shipmates who worked in the same office as I did — shipmates whom I helped with their careers, people with whom I’ve become more than just shipmates and friends,” Scott explains.

“We knew there was a need and we wanted to see what we could do to help combat that. If we have just kept one sailor, soldier, airman or Marine alive for one more day through recreation and bowling, then I know the vision is working.”

Scott has signed on as the organization’s Vice President, and Griner swears by her importance to his cause.

“She’s a good bowler, she’s always been part of the sport, she’s always competing, so when I had the chance to get with her, I said, ‘Why don’t you just hop on board and get with me at Strike Against Suicide?’ and she was all for it,” says Griner, 48. “She’s been my right hand behind the whole process. She’s the Vice President of it, and sometimes I feel guilty about over-tasking her. I put a lot on her plate, because she’s still active duty and she’s got other things she’s doing, but she always manages to get them done. It’s that old saying in the military, when you’re good at what you do, you don’t get breaks; you get more thrown at you.”

At the same time, Griner advises that his cause is not about any single individual, and cautions that the mission will have failed if any one person becomes its backbone. The idea of serving a cause bigger than herself, which entails an awareness that others’ needs will come before hers at least at times, is no hard idea to fathom for someone of Scott’s background.

“I’m the last of eight kids,” she says matter-of-factly in her deadpan manner of speaking. “There were, at one point, four of us who bowled. Two of my brothers, myself, and my sister, but now it’s just myself and my sister who bowl.”

What was it like growing up in a household that included so many children? Simple.

“Chaos,” Scott says, chuckling.

It’s Personal

In an environment like that, you learn quickly that it’s not about you. And her efforts with Strike Against Suicide most certainly are not about her but about those the cause urgently seeks to reach. It is about people like her buddy Ron Condrey, whose story forever will charge her efforts for Strike Against Suicide with an incorrigible drive and commitment.

“When I was just a junior sailor, he was a Chief. I was his retirement clerk. I would work closely with [those nearing retirement] to make sure all of their paperwork was good for retirement, so we spent a lot of time working together and we ended up becoming really good friends, but Ron had spent multiple tours overseas and he was blown up a couple of times, so you could see the battle wounds on his arms and his legs.

“I remember being at the psych ward with him, helping him with his retirement stuff. You only retire once, so you want to get it right. Being around that and forming a great friendship with him, it was a beautiful thing. But he just had those demons and so much going on that he lost his battle with his demons and took his own life, and his wife is an amazing person, the mayor of a small town, and she keeps his memory living on by advocating for mental health. He is one person who has impacted me a lot because you don’t know what suicide looks like. That can look like someone smiling or it could look like someone crying. You would never be able to tell.”

If you hear a certain eloquence in Scott’s speech, you are not alone.

Brad Edelman, whose High Roller, Inc., organization runs the Military Bowling Championships twice each year, provides her with a table, booth space, and a platform during the event’s opening ceremonies to speak on Strike Against Suicide’s behalf.

“She loves speaking in front of people and she is very good at it,” Edelman observes.

Scott also has put in several recent appearances on Phantom Radio to talk up the organization and, along with Griner, continually seeks opportunities to broaden awareness of it.

Overton, drawn to the cause by personal experience despite not herself serving in the military, sees first-hand that Griner’s vision for his organization, driven home by the likes of Scott and others including herself, is working.

“I am seeing veterans come [into the bowling center] with smiles on their faces when they didn’t have smiles before,” she says. “There are veterans who come into the bowling alley and want to bowl but they don’t have shoes, or they don’t want to pay the $10 for shoes every time they come bowling, but they want to learn the sport, they want to be involved with the bowling community, so I think Strike Against Suicide, Spare a Life is giving prospective bowlers and current bowlers an outlet so they can continue, or become, a member of that community.”

That word “community” comes up in every conversation with anyone involved with the organization’s efforts.

For Hawk, 56, who lost his 34-year-old son Derrick to an apparent suicide earlier this year, the reason for that comes down to a basic human yearning for connection.

“The goal is to get them out of the house, or the barracks, or off the ship, and get them interacting with people,” he says of the organization’s appeal to veterans or those still on active duty. “Bowling is our common thread among the group. We all love bowling. We know that there is a bowling community that really gives a damn about people out there, and we’re a part of it.”

Hawk, who provides his project-management expertise to the organization while also handling shipping and receiving, knows firsthand just how widespread that community is. He sees the orders for those shammies and bottles of ball cleaner come in to support the organization’s cause. They come from everywhere.

“We see it across the nation and all over the world,” Hawk says. “All the way over to Idaho, down into California and Texas, in Japan, Hawaii, people are buying stuff and the word is getting out about what we’re doing. It’s just a matter of getting people to realize that there are people who give a damn about them, and we’re trying to get the bowling community to realize that we can help people, and it doesn’t take much.”

Hawk, who followed older brother John into the Navy in 1986 at age 17 and retired in 2008, is as familiar with the bowling community as anyone.

“My dad got us bowling,” he explains. “We moved from Ohio to Tampa, Florida, when I was about 10 years old, and he was a bowler down there. Tommy Crites was the PBA Rookie of the Year in 1985, and he was Tommy’s coach in high school. We kind of grew up with Tommy Crites; he was a generation ahead of us, so he helped coach us when we were kids and I stopped when I was in high school. But, once I joined the military, transferring all the time and going from ship to ship, plus having a young family, I wasn’t able to keep up with it.”

He picked up bowling again around 2004 as he neared retirement, and today carries a 225 average.

Like the military personnel both past and present he hopes Strike Against Suicide impacts, bowling was, at that time in Hawk’s life, “just something to get me out of the house.”

Scott, who has bowled for the Navy for 13 years now and has a 300 game and an 800 series to her credit, knows well the power behind bowling’s ability to just get people out of the house.

“We aim to get sailors, soldiers, airmen and Marines out of their house, barracks and ships because that’s where you spend a lot of time alone. You’re alone with your thoughts. And sometimes, that is not good. What we want to do is create a safe environment where these service members can get out of those [isolating] locations and join other service members and destress, recalibrate, and be around like-minded individuals.”

That point about like-minded individuals is especially resonant for members of the unique cadre that military personnel comprise.

“It’s easier to have conversations about what we’re going through with other military members who can relate,” Scott explains. “That’s not to say that some civilians can’t relate, but they don’t know what they don’t know. They can only imagine. They can only sympathize.

“But those sailors, those people who have been going through it, they’ve been on the same deployment, they’ve been out to sea for any number of months, they’ve been stationed overseas away from their families, so we just aim to get them out of the house and around like-minded individuals and support their mental health through recreation. We do that by paying for their time on the lanes, giving them bowling balls to start their bowling journey, or bowling shoes, ball cleaner, swag, all those things that will help them use recreation as a form of mental-health treatment.”

Stigma

If there is a stigma attached to depression or suicidal ideation among the general public, that stigma intensifies exponentially among those in uniform.

As Jay Miller, a scratch bowler now in his 15th year with the Navy, explains, “In the military, you’re held to a higher standard. And sometimes, when you’re held to a higher standard, it could be a little frightening to have these thoughts and worry that people are going to think that you’re weak because of that. You worry that people are going to think less of you. So, they tend to keep those feelings bottled up because they don’t want people to feel that way about them.

“But we want people to know that they’re not going to be judged just because they’re having those thoughts. We’re here to help you know that those thoughts are valid and know why they are important and why it is important that they are here.”

Miller serves Strike Against Suicide as a promotion advisor, finding ways to get the word out about the organization and what it does.

“My goal is to reach as many people as I can with my networking and my military experience and just talk to individuals to help them understand that they are not alone,” he says.

Hawk, too, is all too familiar with the reasons military service members often are more given to bottling up their darker thoughts than they are to voice them or even display the slightest outward evidence of the turmoil within themselves.

“The military trains us to basically be emotionless,” he says. “We need to be able to do things [that require a certain stoicism], and we might be feeling something on the inside, but let’s not show that on the outside. In some societies, and in parts of our own society, that’s perceived to be part of being ‘a man,’ or part of being ‘an adult.’

“But the reality is that we become experts at hiding what’s going on inside. So, we’ve got to be able to let people know, we’ve got to reach out to them and draw those feelings out so that we can discuss them and put them to bed.

“I myself have been unsuccessful at doing that more times than I want, with friends and even with my son, who suffered with depression and had suicidal ideation many times in his adult life. I wasn’t able to get him away from the demons in his head.

“It’s the same thing with [Ron Condrey]. He sought treatment but it didn’t cure what was going on inside of his head because of several traumatic brain injuries he suffered, and eventually he lost his battle.

“So, we’ve got to be able to get these people to talk. Like Ashley says, if we save one, it doesn’t matter how much time we spend trying to do that. If we save one, it will be worth it, because that one person isn’t finished with what they’re set out to do on this Earth. They’re not done. We’ve got to make sure that they realize that.”

Scott, too, understands what a tall order that can be among military service members.

“In the military, you’re supposed to be so tough, right? We’re training war fighters. You’re supposed to be bad to the bone. And when someone in the military is going through those things, they’re not going to talk about it and they’re not going to seek help because it exposes them to the perception that they are weak.

“And war fighters aren’t weak. We don’t win wars by being weak, right? So, they would rather not say anything and not talk about it because of perceptions about what they are supposed to be.”

It is clear that such an approach to managing their demons is not working. In the first three months of 2024, suicide claimed the lives of 94 active service members, 24 reserve members, and 21 serving in the National Guard. Yet, even had some of them sought help, it might not necessarily have been readily available, and this is another problem Scott identifies as a reason for the scourge suicide has become throughout the military.

There is, Scott explains, a “lack of military treatment facilities, and a lack of qualified people to provide treatment, like doctors. When something as simple as getting my eyes checked is booked three months out, can you imagine someone really needing a mental-health appointment and being told it will be five months? Well, guess what? That person might not be around in five months. There are service members who are going out into the civilian sector and paying out of pocket for mental-health treatment because we are so backlogged and there are not enough providers to handle the amount of sailors who are looking to get help.”

Military Bowling Championships

One event held twice annually — each January and again each August — provides some degree of help, however small, to those looking to capture a piece of that bowling community which, as Hawk says, gives a damn about them. That event is the Military Bowling Championships, and it amplifies and embodies Strike Against Suicide’s mission to use bowling as a gathering point around which service members can enjoy the healing benefits of social interaction with people of similar backgrounds and life experience.

Brad Edelman, whose High Roller, Inc., organization took over the event in 2005 following the closure of its host The Castaways (formerly The Showboat) in Las Vegas, saw more than 6,200 bowlers shoe up for his August event at South Point in Las Vegas, which, unlike the January edition, does allow non-military “guests” to mix in with the active and veteran service members who bowl.

“We have grown it, and the one in January is now known as the largest participation of military personnel in a sporting event in the world, and we were told that by the Department of Defense,” says Edelman, who calls the experience of running his Military Bowling Championships “humbling.”

He explains that, at any given Military bowling Championships tournament, “You never know who you’re speaking to. Somebody will come up to you in shorts and a t-shirt ready to bowl, and in a previous life he was a three-star somewhere.

“We’ve met people who openly will tell you they’ve killed 300 people, and somebody else will say he was in a troop where half his troop was killed. The things you hear and the people you meet, it makes you really think about the phrase, ‘Thank you for your service.’ Well, until you realize what that service actually is, it’s just mind-boggling.”

Edelman explains that his participants, by and large, do not even come to the event for the bowling but rather for the very benefits Strike Against Suicide attributes to the sport. Hawk, for his part, is one such example.

“I’ll tell you this: I am a scratch bowler, and the August tournament is a handicap tournament. Unless I’m shooting 900, there’s no way I’m going to win that tournament. That’s not my purpose for going. My purpose for going is to see the people that I’ve served with, fellow bowlers that I have served with previously, and meet new ones. There’s always somebody out there with a story to tell, and it is so prevalent,” he says.

“When Ashley and I were out there raising money by selling merchandise this past August, we had people come up to us and tell us stories. One guy said that on that date a few years ago, he sat down on the couch in his front room and was about to [take his own life] when he looked up and saw Christmas lights across the street and he stopped what he was doing because he remembered that his granddaughters just love Christmas.”

Would a civilian understand that story as deeply as a military service member?

“I’m sure they could on some level,” says Hawk, “but would someone who was a non-veteran walk up to that merchandise table and tell you that story? Chances are that they would not, because they’re not going to get that personal with you. You don’t have that type of connection with them. The military connection isn’t something that can be related to. You can’t say, ‘Oh yeah, we went on vacation for two weeks and we have this connection just like they do in the military.’ Absolutely not. These veterans fought for each other just to stay alive.”

Which is the very connection and community that events like the Military Bowling Championships harness.

Miller says the tournament “gives us a chance to see military people that we don’t get to see everyday. It gives a chance for all of us — active duty, reserve, retired or just veterans — to come back and reconnect and have fun doing it. And it’s in Vegas, so you’re also getting the chance to experience that lifestyle as well with the people you might have gone to war with or were on deployment with.”

And the age range the participants comprise each year is almost incomprehensibly vast. The most recent January tournament, Edelman reports, included eighteen bowlers who were at least 90 years old. It was the 68th annual Military Bowling Championships, which began at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas.

Overton hopes that someday soon Strike Against Suicide’s reach also can include children of military veterans, as the educator within the Norfolk, Virginia, public school system says that is a place “where the military population is very high, and I see a lot of students struggle with a parent being deployed and missing them, so I feel as though this organization can help that, too. If nothing else, it can provide those children an outlet.”

Griner’s vision includes a day when his organization can pay for veterans’ lineage at bowling centers, because, as he puts it, “In return for that, I get these guys and gals to get out, socialize, bowl, have that interaction, and that could mean the difference between that and sitting at home, drinking a fifth of whiskey, tying a rope around their neck and hanging themselves. Small things make a difference.”

In the meantime, Miller is emphatic in his hope that the organization’s efforts will make a positive impact on suicide rates among military service people.

“I wouldn’t be a part of this organization if I didn’t believe it could help in some way,” he says. “I believe that there is a path forward for the numbers of suicides in the military to go down, and I think Strike Against Suicide is on the right path. I’ve witnessed first-hand sailors who have had suicidal thoughts and, because they decided to branch out and believe in the organization, now they are on the other end of it. And now, they’re talking to other sailors, soldiers and airmen about their experiences.”

As Overton puts it, “I’ve had conversations with some outside the bowling alley who have told me that if it weren’t for bowling, having somewhere to go and experience that community and take out some frustration on the lanes, they don’t know if they would be here.”

Everyone working with Striking Against Suicide, Spare a Life is elated that they are still here, and wants those on the brink to know that they, too, have an unfinished purpose to pursue in this world.

Those interested in learning more or helping the cause can go to strikeagainstsuicide.com to do so.