Taking Care of Our Own: When the Local Bowling Community Helped Parkland Heal

On Friday, Feb. 16, 2018, Sam Stein, the politics editor for The Daily Beast, tweeted the following: “This week was awful. Just awful. All of it.”

They were just nine simple words, but they expressed a reservoir of emotion which, by then, I had been struggling to work through for a good 48 hours. It is a struggle that has become all-too familiar for me since I began my position as Editor of BJI in 2014.

Once again, I somehow had found my way to the end of a workweek during which another American horror story unfolded on my television. This time, on Valentine’s Day of all days, 17 people had been gunned down at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. — most of them students, others teachers and coaches, all of them people whose lives were unfinished.

Too often over the past few years, I have had to struggle to work through this same story. It is the story of people gathered together in places of joy that become places of dread — a night club, a country music festival, a church.

Hannah Carbocci’s friend Helena Ramsay was in the same classroom as Hannah when the shooting broke out.

Hannah Carbocci’s friend Helena Ramsay was in the same classroom as Hannah when the shooting broke out.

I did not know why the story of what happened at Stoneman Douglas hit me even harder than the others. I tried to figure it out. Maybe because I myself was a teacher for years before turning my attention to journalism full-time. Maybe because I am the father of a four-year-old girl now. Maybe because I live just a 90-minute drive from Stoneman Douglas. This one felt closer to me, more haunting, more difficult to work through.

As I mulled over those maybes, there was one thing I knew for sure: I still had deadlines to meet, people depending on me to get my work done and to do it well, stories that needed to be written. Life carries on because it must. It always does. No matter what.

In the midst of pushing on with those obligations, I received an email about a five-time PBA Regional champion who happens to live and teach math to middle schoolers within five miles of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Here, perhaps, was someone who might be able to help me make a little sense of the senseless. I called and left him a message.

He called me back the next day. When I answered, I could tell he was calling me while on the road. Michael Azcarate, who would shoot 856 in league a few weeks later with games of 279, 289 and 288, was on his way to a bowling tournament.

Many of the things he told me were stark, blunt, sad, disturbing and, frankly, kind of painful to hear. But so was the week that he and his community had just lived through. I listened.

PBA Regional champion Michael Azcarate knew some of the students at Stoneman Douglas because they bowl a scholarship tournament he puts on annually in memory of Ryan Boyd, a friend who succumbed to cancer in 2014.

PBA Regional champion Michael Azcarate knew some of the students at Stoneman Douglas because they bowl a scholarship tournament he puts on annually in memory of Ryan Boyd, a friend who succumbed to cancer in 2014.

A father of six in addition to being a teacher, Azcarate explained that he knew some of the students at Stoneman Douglas because they bowl a scholarship tournament he puts on annually in memory of Ryan Boyd, a friend who succumbed to cancer in 2014.

One of those students is 17-year-old junior Hannah Carbocci, a bowler aspiring to compete for close family friend and five-time PBA Tour champion Bob Learn Jr., who had been a presence on the South Florida bowling scene when he lived there before taking his new gig as head bowling coach at Martin Methodist College in Pulaski, Tenn., in 2017. Hannah’s father Brady has been a friend of Azcarate’s for 30 years.

Hannah hid under her teacher’s desk when the shooting broke out, thumbing panicked text messages to her 19-year-old sister Kaitlin, herself a Stoneman Douglas graduate.

At first, Hannah had trouble getting Kaitlin to believe her. “hannah what are you serious rn,” Kaitlin texted. Hannah replied, “kaitlin I am not joking they just shot through the walls someone in my class is injured.” Later in the exchange, Kaitlin texted, “i love you so much.” Hannah replied, “im so scared i cant make any calls i love you.” When Kaitlin assured Hannah that “daddy is in response,” Hannah replied, “tell them i love them so much.”

Hannah, struggling to speak through tears, later spoke on-camera with CNN’s Alisyn Camerota outside Stoneman Douglas. “I wanted my family to know that I loved them so much, and that if anything were to happen to me, I would be okay,” she said.

Hannah survived. Two others in her classroom did not. Their names were Helena Ramsay and Nicholas Dworet. Both were 17 years old.

Azcarate seems to choke up a bit on the phone.

“It’s just,” he says. He pauses, then tries again. “It’s just heartbreaking. It’s very emotional when you just read . I know her, and I know her family.”

He also knows the kind of place that is Stoneman Douglas High School.

“It’s an affluent community, it’s a small community, it’s a very large school, there is a lot of parental involvement,” he says. “My daughters went to a neighboring school, and they were in the band. Stoneman Douglas’s marching band is the one that all the other schools in the state aspire to be like.”

Prior to the shooting, the Stoneman Douglas Wind Symphony Band successfully had auditioned to become one of six high school bands from across the country selected to perform at Carnegie Hall in New York City. They did so on March 6. That same night, bowling league with his “Brady’s Bunch” team at Sawgrass Lanes in Tamarac, Fla., Brady Carbocci shot his 39th perfect game.

CBS Miami reported that the Stoneman Douglas band’s director, Alex Kaminsky, thought about canceling the trip after the shooting but said, “It became evident to me that these kids needed to get together to play.”

“It’s a really tight-knit, strong school,” says Azcarate, who teaches at Millennium Collegiate Academy, which he says is “five or six miles” from Stoneman Douglas. “I’ve actually had conversations with my students because, the next day, all the schools in Broward County were on a soft lockdown. It’s called a ‘code yellow.’ There’s limited movement, only movement with an adult escort.

“I try to impress upon my students that, statistically, their school is safe. But if someone is going to do something bad, there’s not really anything you can do. We have trainings, we have drills. We do all these things. But it’s something that you still can’t prepare for.”

Azcarate explains the intensity of those drills in a way that makes all the more palpable the kind of fear Hannah Carbocci expressed in text messages to her sister.

“To me, it’s crazy that I am even saying this. We have ‘active killer trainings’ in our schools,” Azcarate says of drills that involve cops shooting blanks. “Once 911 is called it takes police two to three minutes to get to the school, and they run a timer. They let you see just how long that is. Everybody takes for granted how little time two to three minutes is. But if you’re in a situation where you hear gun shots and you smell gunpowder, two to three minutes is an eternity. That’s what those children and those teachers had to go through.”

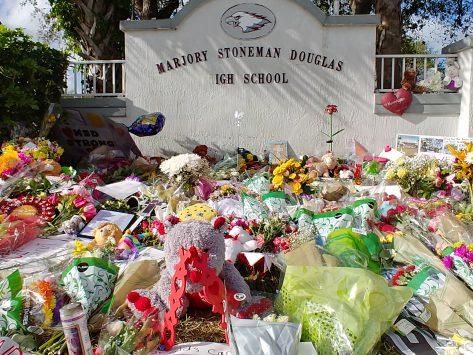

The Stoneman Douglas High School shooting memorial site was smothered with teddy bears, flowers, candles, and handwritten remembrances and prayers.

The Stoneman Douglas High School shooting memorial site was smothered with teddy bears, flowers, candles, and handwritten remembrances and prayers.

Azcarate began teaching 19 years ago after taking his shot on the PBA Tour in the ‘90s, when he roomed with the likes of Jason Couch, Doug Kent, Parker Bohn III, and Mike Miller. He says he left the tour and headed home to get his teaching degree when he realized he “wasn’t going to be the next Pete Weber.” The “active killer trainings” he has experienced since were not among the responsibilities he thought he was taking on when he got his degree.

“Basically, what we’re trained to do is keep the children out of sight for as long as we can until law enforcement can get there to neutralize the threat. I mean, it’s a crazy training. I have been told by police officers who give the training that, once they start, there are adults who have soiled themselves, crying, vomiting, just from the fear. And this is just a simulation. I could not imagine what those teachers and students actually went through. The fear and the trauma have to be absolutely unfathomable … those children will never be the same.”

Days after I spoke with Azcarate, a man named Fred Guttenberg appeared on “Morning Joe,” the cable news program with which I tend to begin most workday mornings while helping get my daughter ready for preschool. Guttenberg’s daughter Jaime was among the victims of the Stoneman Douglas shooting. She was 14 years old. “My house is broken, and I don’t know how we fix it,” Fred said. Then he talked about what Jaime wanted to do with her life. How much she loved dance. How she wanted to become a therapist for people suffering from physical deformities.

As Guttenberg kept talking, I told my daughter I needed a hug. She leapt onto my lap and wrapped her arms around my neck, hugging me tight. Then she asked a question. “Why?” she said. Sometimes the simplest questions children ask are the hardest for parents to answer.

I got her dressed. My wife did her hair and got ready to drive her to school. Then my daughter walked up to me, looked up and puckered her lips for a kiss goodbye. Something occurred to me in that moment: It really was not so long ago that the teens killed at Stoneman Douglas were tiny children like my daughter. Children like Jaime Guttenberg or Helena Ramsay whose mothers had braided their pigtails on mornings like this one, packed their lunches, sent them off to class wearing Hello Kitty backpacks.

I waited to hear the door close behind my daughter and my wife as they left. Then I let out a deep breath, sat at the dining room table and cried.

When Azcarate put me in touch with Hannah Carbocci’s father Brady, himself a lifelong bowler who was a roommate of PBA champions such as Bob Vespi and Steve Wilson on tour in the ‘90s, I wanted to ask him how a parent even begins to talk a child through the emotions and the trauma that accompany an experience such as the one Hannah survived. As a father myself, I needed to know.

“When I got to the scene and found her walking down the street with no shoes on and in complete hysterics, I just wrapped my arms around her, gave her the tightest hug and told her to breathe and to calm down,” he says. “From the beginning, I’ve been telling her to keep the faith and that everything’s going to be alright. That’s pretty much all you can do. I wasn’t in her shoes, so I couldn’t really relate in that sense. But I could just tell her how we felt as parents. The panic and wondering, you know, if your child’s going to make it out of there or not.

“It was the worst phone call I ever got in my life,” Brady adds. “The worst one, other than the passing of my mom, was my brother. He’s a deputy who was shot back in 2006 and that was a real hard time for the family. But this call that I received from Kaitlin saying that there was not only an active shooter on campus, but that her classroom had actually been shot into and there were people lying injured and, we would later find out, dead all around her in that very classroom, it kind of sent me into panic mode.”

Hannah Carbocci, here with dad Brady, hopes to bowl for close family friend Bob Learn Jr.’s team at Martin Methodist College in Pulaski, Tenn., after graduating from Stoneman Douglas.

Hannah Carbocci, here with dad Brady, hopes to bowl for close family friend Bob Learn Jr.’s team at Martin Methodist College in Pulaski, Tenn., after graduating from Stoneman Douglas.

Brady’s brother, Corey, has since recovered from his injuries and was among the responders to Stoneman Douglas. He put his own life at risk as he helped remove kids from the school before the shooter’s whereabouts were known. Brady calls him a hero.

"I really had to take a lot of deep breaths to calm myself down on the ride over because there was so much going through my mind,” Brady says. “When your child is in a life-threatening situation and you can’t do anything for them, it’s just a feeling that no parent should ever have to feel.”

Brady cannot turn back the grief of fellow Stoneman Douglas parents whose children did not survive the horror from which Hannah escaped. But he did not let that stop him from taking action.

“It’s a parent’s worst nightmare, having to bury a child. Nobody should have to do that,” he says. “We just thought, ‘What can we do, no matter how big or how small, to show how thankful we are that our daughter’s still here and that we feel for the victims’ families? What can we do for them, to ease their pain just a little bit?’

“Since I’ve been a bowler my whole life and my kids have been bowling for many years now, we’ve been around a lot of great people and we’ve been part of fundraisers, bowling in tournaments that have supported different causes over the years,” he continued. “It just came to mind to reach out to a lot of the pro-shop owners in the area who I’ve had the pleasure of bowling leagues and tournaments with over the years, and I thought maybe I could put out a Facebook post asking if somebody could give us a hand by donating some bowling balls so we could do some raffles.”

Within five minutes of making that Facebook post, at least six people had offered to donate bowling balls.

“We were just overwhelmed by donations of bowling balls to do the raffles,” he says.

A mere two weeks later, Brady and wife Stacy, along with Hannah and Kaitlin, had helped raise $15,583 for the Broward Education Foundation. Through that organization, the money went to the Stoneman Douglas Fund for victims’ families. Among those who donated balls was Azcarate, who donated one on behalf of the Ryan Boyd Memorial Scholarship Fund for which he serves as president.

“The financial burden can be very difficult and unexpected, in addition to all the mental and emotional pain these families are going through,” Brady said. “I didn’t know how much money we were going to raise. I didn’t in my wildest dreams think we were going to get close to that number.

A two-hander himself, 9-year-old Lorenzo Carbocci is a big fan of Jason Belmonte, who gave him a surprise phone call after learning what the Carboccis had been through.

A two-hander himself, 9-year-old Lorenzo Carbocci is a big fan of Jason Belmonte, who gave him a surprise phone call after learning what the Carboccis had been through.

“We have to thank the bowling community and all the people who were kind enough to donate these bowling balls for the cause. I can’t say enough good things about them. I see them on a nightly basis in leagues and tournaments; some of them are my closest friends. They’re just fantastic people, and they always get behind the cause.”

Brady’s tremendous gesture was returned by an unexpected source. When Jason Belmonte learned that Brady’s 9-year-old son Lorenzo is a two-hander who is, as his dad put it, “very fond of Jason Belmonte,” Belmonte gave the family a surprise phone call.

“We had a nice chat with him,” Brady says. “He is a very generous person. He’s sending new Storm Bowling balls and bags to the kids. They were so excited to speak with him, as were we.”

Sam Stein was right. That week was awful. Just awful. All of it. There is something else that is just as true. When something devastating impacts a member of the bowling community, we take care of our own.

This story ran in the April 2018 issue of Bowlers Journal International. To subscribe now for much more of the industry's best coverage of bowling news and incisive instructional tips and analysis, go here: /bowlers-journal-subscriptions/