The coolest dude in the room

March 31, 2024

James Dean was cool. So was Paul Newman. Ditto for Muhammad Ali, James Brown, Clint Eastwood and Johnny Depp. And let’s not forget The Fonz, or Snoopy’s alter ego, Joe Cool.

Each exuded coolness in his own way, but each shared certain qualities that seem to be universal among cool people: confidence, total emotional control, grace under fire. It’s difficult to define precisely. You just know it when you see it.

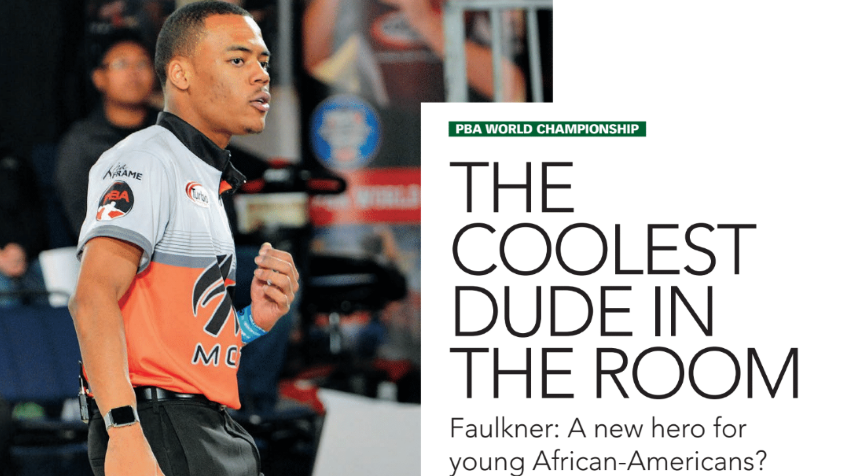

We saw it on Dec. 17 when the Professional Bowlers Association returned to prime time television for the first time in 14 years. Gary Faulkner Jr. was the coolest dude in the room — the big room of the National Bowling Stadium in Reno — as he rolled to victory in the Rolltech PBA World Championship.

The fact that Faulkner is an African-American made the accomplishment historic. In the 57-year history of the PBA, only one other black player, George Branham III, had captured a title. Branham, who now works for Pepsi Cola in Indianapolis, finished his career with five titles, the first being the 1986 Brunswick Memorial World Open.

The fact that it took 29 years for history to repeat speaks to how bowling is perceived as a sport, according to Branham.

“I played basketball and football as a kid, and I bowled,” Branham says. “I had a passion for bowling, but you never heard about bowlers making millions of dollars a year like players in basketball, football and baseball. I think that’s why most black kids played other sports.”

Bowling, he adds, is largely invisible in the African-American community, in part because it’s expensive to play.

“You can’t just grab a ball and find a basketball court,” he notes. “You have to pay by the game, and the only way to get good is to bowl a lot of games.”

Like Branham, Faulkner has a passion for bowling. But Faulkner does not count Branham among his role models because he was only 6 years old at the time Branham won his last title. His childhood bowling hero was Parker Bohn III, a fellow left-hander.

Bohn is known for his strong mental game. That’s why he ranks fifth on the PBA’s all-time titles list, and first on its all-time 300s list. It’s a trait that Faulkner shares, and it helped keep him focused on the task at hand: knocking down pins, ignoring distractions (including one fulminating drunk in the bleachers), and not worrying about what his opponents were doing during his first-ever PBA television appearance.

On shot after shot, resulting in strike after strike, Faulkner looked as if he didn’t have a care in the world. He admits to being nervous on his first shot — a trip-6 strike — but says he was fine after that.

His first opponent in the stepladder finals was fellow southpaw, Scott Norton, who had defeated Rhino Page in the opening TV match, 215-202. Faulkner followed that first strike with four more before leaving a 4-6-10 split in the 6th frame. That opened the door ever so slightly for Norton, but Faulkner quickly closed it by running off another five-bagger, a string ended by another 4-6-10 on his 10th-frame fill ball. The final score: 262-218.

Ryan Ciminelli, seeking a second major title that would make him a strong contender for 2015 PBA Player of the Year honors, proved to be a much stronger opponent in the next match. After registering just one strike in the first half of the game, Ciminelli ran off a five-bagger that was stopped by a light 10-pin. He finished with a 237 score, forcing Faulkner to mark in his 10th frame for the win. Faulkner sent his shot through the nose, but avoided disaster by leaving only the 7-pin, and advanced to the title match against the top seed, E.J. Tackett, with 247.

It was an unusual match-up as it pitted a left-handed bowler who had to deal with oil transition against a right-handed bowler whose side of the lane had been virtually untouched in the first three matches.

Ultimately, the adjustments Faulkner needed to make were subtle. Tackett, on the other hand, never had a good look until the 6th frame. In the first half of the game, he rolled no strikes, came in light four times (leaving the 2-8-10 twice, the 2-4-10 and the 2-pin) and went through the nose once (leaving the 3-6). By the time he finally figured out which ball he should be throwing, he was hopelessly behind. Tackett recorded four strikes in the last five frames, but Faulkner simply coasted to a 216-178 victory.

Faulkner had enjoyed success at every level of the sport, initially by dominating junior competition in the Southern Region of TNBA — a bowling organization consisting primarily of African-Americans — for seven years. He won the 2011 USBC Junior Gold Championships to earn a berth on Junior Team USA, and the next year led Webber University to the USBC Intercollegiate Team Championships, taking down perennial powerhouse Wichita State in the championship match. Faulkner, bowling anchor, seemed to strike whenever the Warriors needed one, including in the 10th frame of the title match.

“I just got up there, pointed and shot,” he said at the time.

Kegel’s Del Warren, the head bowling coach at Webber, described Faulkner as extremely coachable, which meant making minor changes to his already solid game were easy.

“His swing used to be behind his back, and the over-clocking of his hand caused too much tilt and rotation at times,” Warren says. “We also got him rolling the ball a little bit more so he could play outside and on shorter patterns a little more effectively.”

That was a tweak that came in handy in the World Championship, as most of the left-handers were playing somewhere between the five and 10 boards.

Adds Warren: “We miss him not just because of the player he is, but because he’s a good person and a great teammate.”

Solid player. Good person. Great teammate. And now, to that list, you may add: role model.

“I was up for hours the night he won, looking at all the posts and shares on Facebook,” says Team USA Assistant Head Coach, Kim Kearney, who helped blaze a trail for African-American women on the Ladies Pro Bowlers Tour and Professional Women’s Bowling Association circuit.

“First of all, he is just a great young man who is extremely liked and respected among his peers. But more moving to me were the many who responded, young and old, who only know him from afar. He is proving to be a symbol for so many who maybe didn’t have the opportunity to follow their dreams, and we all know someone like that.

“I had a friend who posted that, growing up, he had me, George [Branham], Cheryl [Daniels] and Curtis [Odom] to look up to,” Kearney adds. “He wondered if Gary would be the player for this generation to idolize. It has been a long time since a kid who looks like us has had someone to identify with in bowling. We all need heroes.”

In that regard, Faulkner says he is up for the challenge, although he adds that it’s really nothing new.

“Just being a professional bowler, I’ve felt it was my responsibility to be a role model, not just for African-American kids, but for everyone,” he says. “I’m pretty easy going; I don’t lose my temper much.”

That’s a trait that impressed Branham, who says he happened upon the World Championship telecast almost by accident, then stayed with it because he saw Faulkner bowling.

“I hope it doesn’t take as long to get a third [African-American] champion as it took to get a second,” Branham says. “I never worried about that part of it; I was just trying to win a PBA title. That’s what Gary should do. Don’t look at it as being a black role model. Just be the best pro bowler you can be. The rest will take care of itself.”

Faulkner, who also has a PBA Regional title on his resumé, adds that he felt it was only a matter of time before he’d break through for his first national win.

“I knew that I could do this,” he says. “I’ve visualized it. I’ve seen it.”

Faulkner, like the other four finalists, had to wait the better part of a day before the World Championship’s prime-time telecast on ESPN. How did he pass the time prior to the warm-up session?

“Around noon, I got a little bit nervous,” he admits. “That lasted for about a half-hour. Then I took a nap.”

Now that’s cool.

Each exuded coolness in his own way, but each shared certain qualities that seem to be universal among cool people: confidence, total emotional control, grace under fire. It’s difficult to define precisely. You just know it when you see it.

We saw it on Dec. 17 when the Professional Bowlers Association returned to prime time television for the first time in 14 years. Gary Faulkner Jr. was the coolest dude in the room — the big room of the National Bowling Stadium in Reno — as he rolled to victory in the Rolltech PBA World Championship.

The fact that Faulkner is an African-American made the accomplishment historic. In the 57-year history of the PBA, only one other black player, George Branham III, had captured a title. Branham, who now works for Pepsi Cola in Indianapolis, finished his career with five titles, the first being the 1986 Brunswick Memorial World Open.

The fact that it took 29 years for history to repeat speaks to how bowling is perceived as a sport, according to Branham.

“I played basketball and football as a kid, and I bowled,” Branham says. “I had a passion for bowling, but you never heard about bowlers making millions of dollars a year like players in basketball, football and baseball. I think that’s why most black kids played other sports.”

Bowling, he adds, is largely invisible in the African-American community, in part because it’s expensive to play.

“You can’t just grab a ball and find a basketball court,” he notes. “You have to pay by the game, and the only way to get good is to bowl a lot of games.”

Like Branham, Faulkner has a passion for bowling. But Faulkner does not count Branham among his role models because he was only 6 years old at the time Branham won his last title. His childhood bowling hero was Parker Bohn III, a fellow left-hander.

Bohn is known for his strong mental game. That’s why he ranks fifth on the PBA’s all-time titles list, and first on its all-time 300s list. It’s a trait that Faulkner shares, and it helped keep him focused on the task at hand: knocking down pins, ignoring distractions (including one fulminating drunk in the bleachers), and not worrying about what his opponents were doing during his first-ever PBA television appearance.

On shot after shot, resulting in strike after strike, Faulkner looked as if he didn’t have a care in the world. He admits to being nervous on his first shot — a trip-6 strike — but says he was fine after that.

His first opponent in the stepladder finals was fellow southpaw, Scott Norton, who had defeated Rhino Page in the opening TV match, 215-202. Faulkner followed that first strike with four more before leaving a 4-6-10 split in the 6th frame. That opened the door ever so slightly for Norton, but Faulkner quickly closed it by running off another five-bagger, a string ended by another 4-6-10 on his 10th-frame fill ball. The final score: 262-218.

Ryan Ciminelli, seeking a second major title that would make him a strong contender for 2015 PBA Player of the Year honors, proved to be a much stronger opponent in the next match. After registering just one strike in the first half of the game, Ciminelli ran off a five-bagger that was stopped by a light 10-pin. He finished with a 237 score, forcing Faulkner to mark in his 10th frame for the win. Faulkner sent his shot through the nose, but avoided disaster by leaving only the 7-pin, and advanced to the title match against the top seed, E.J. Tackett, with 247.

It was an unusual match-up as it pitted a left-handed bowler who had to deal with oil transition against a right-handed bowler whose side of the lane had been virtually untouched in the first three matches.

Ultimately, the adjustments Faulkner needed to make were subtle. Tackett, on the other hand, never had a good look until the 6th frame. In the first half of the game, he rolled no strikes, came in light four times (leaving the 2-8-10 twice, the 2-4-10 and the 2-pin) and went through the nose once (leaving the 3-6). By the time he finally figured out which ball he should be throwing, he was hopelessly behind. Tackett recorded four strikes in the last five frames, but Faulkner simply coasted to a 216-178 victory.

Faulkner had enjoyed success at every level of the sport, initially by dominating junior competition in the Southern Region of TNBA — a bowling organization consisting primarily of African-Americans — for seven years. He won the 2011 USBC Junior Gold Championships to earn a berth on Junior Team USA, and the next year led Webber University to the USBC Intercollegiate Team Championships, taking down perennial powerhouse Wichita State in the championship match. Faulkner, bowling anchor, seemed to strike whenever the Warriors needed one, including in the 10th frame of the title match.

“I just got up there, pointed and shot,” he said at the time.

Kegel’s Del Warren, the head bowling coach at Webber, described Faulkner as extremely coachable, which meant making minor changes to his already solid game were easy.

“His swing used to be behind his back, and the over-clocking of his hand caused too much tilt and rotation at times,” Warren says. “We also got him rolling the ball a little bit more so he could play outside and on shorter patterns a little more effectively.”

That was a tweak that came in handy in the World Championship, as most of the left-handers were playing somewhere between the five and 10 boards.

Adds Warren: “We miss him not just because of the player he is, but because he’s a good person and a great teammate.”

Solid player. Good person. Great teammate. And now, to that list, you may add: role model.

“I was up for hours the night he won, looking at all the posts and shares on Facebook,” says Team USA Assistant Head Coach, Kim Kearney, who helped blaze a trail for African-American women on the Ladies Pro Bowlers Tour and Professional Women’s Bowling Association circuit.

“First of all, he is just a great young man who is extremely liked and respected among his peers. But more moving to me were the many who responded, young and old, who only know him from afar. He is proving to be a symbol for so many who maybe didn’t have the opportunity to follow their dreams, and we all know someone like that.

“I had a friend who posted that, growing up, he had me, George [Branham], Cheryl [Daniels] and Curtis [Odom] to look up to,” Kearney adds. “He wondered if Gary would be the player for this generation to idolize. It has been a long time since a kid who looks like us has had someone to identify with in bowling. We all need heroes.”

In that regard, Faulkner says he is up for the challenge, although he adds that it’s really nothing new.

“Just being a professional bowler, I’ve felt it was my responsibility to be a role model, not just for African-American kids, but for everyone,” he says. “I’m pretty easy going; I don’t lose my temper much.”

That’s a trait that impressed Branham, who says he happened upon the World Championship telecast almost by accident, then stayed with it because he saw Faulkner bowling.

“I hope it doesn’t take as long to get a third [African-American] champion as it took to get a second,” Branham says. “I never worried about that part of it; I was just trying to win a PBA title. That’s what Gary should do. Don’t look at it as being a black role model. Just be the best pro bowler you can be. The rest will take care of itself.”

Faulkner, who also has a PBA Regional title on his resumé, adds that he felt it was only a matter of time before he’d break through for his first national win.

“I knew that I could do this,” he says. “I’ve visualized it. I’ve seen it.”

Faulkner, like the other four finalists, had to wait the better part of a day before the World Championship’s prime-time telecast on ESPN. How did he pass the time prior to the warm-up session?

“Around noon, I got a little bit nervous,” he admits. “That lasted for about a half-hour. Then I took a nap.”

Now that’s cool.